Lobby of Numbers: St. Louis Cardinals

Saturday, January 25 2020 @ 08:00 AM EST

Contributed by: Magpie

The Cardinals have a long history, full of glory and accomplishment. No National League team has won more championships, and only the Yankees have

more titles than the eleven brought back to St.Louis.

Naturally, it didn't start that way.

The St. Louis franchise joined the National League in 1892, after operating for ten years in the American Association. They were known as the Browns, which may explain why they sucked so badly. By the time 1921 rolled around, they'd posted 24 losing seasons out of 29. All that was about to change. In 1917, Sam Breadon had purchased a minority share in the franchise - by 1920, he had bought out his partners and taken control of the team. Already there was Branch Rickey, who had joined the Cardinals as team president in 1917.

Rickey is one of the towering figures in the game's history, fit to be discussed at book-length rather than the paragraph I can spare here. He was a failure as a player, as a lawyer, and as a field manager. But as an operator, he changed the game completely. In Brooklyn, as everyone knows, he integrated his team and shattered the the colour barrier that had kept so many of the game's greatest players outside the major leagues. In St. Louis, he invented the farm system. Both innovations were wildly controversial. Rickey always maintained that the farm system was prompted by necessity more than anything else. The Cardinals didn't have and couldn't afford the network of scouts other teams had, nor could they afford to buy the best players from the minor league operators. What they could afford was to take over failing minor league teams, and use them to find and develop talent. Rickey would spend years fighting with commissioner Landis over all the minor league teams his Cardinals controlled.

When Breadon took control of the team in 1920, he assumed the team presidency that had been held by Rickey, who moved into the dugout as field manager. Almost the very first thing Rickey did was make Rogers Hornsby, a promising young hitter but not a good defender, a full-time second baseman. Hornsby had been playing shortstop and third base for the Cardinals. At the less demanding spot of second base (yes, the game was different back then!) Hornsby absolutely exploded on the league. In 1920 he hit .370/.431/.559, leading the league in all three categories. And from that already impressive height, Hornsby got even better. Over the next five seasons, the Rajah averaged ,402/.474/.690 - seriously, that was his five year average - leading the league in all three categories every year. It's sort of like the slash line Triple Crown and Hornsby won six of them in a row as a Cardinal as well as one more later in his career. It's an accomplishment with no equal in the history of the game (Ted Williams did it five times, Wagner and Cobb four times, Bonds and Musial twice.). Hornsby even managed a pair of traditional Triple Crowns during his St.Louis years.

Rickey's 1921 team finished third but their 87-66 record was the best in the franchise's 30 year history. They pretty much matched that performance the following year when Rickey, who had taken an interest in what we now call "analytics" as far back as his days running the Browns, responded to a shortage of starting pitching by using relief pitchers more frequently than any manager in the game's history had done before him. The 1922 Cardinals were the first team ever to average the use of one reliever per game. That was also the year when Rickey introduced the famous team logo with the two redbirds sitting on the bat, based on something he'd seen in a church the previous winter. But Rickey, a Bible-thumping teetotaler, was not well suited to the daily field management of a baseball team. The team slipped to fifth place in 1923, sixth place in 1924, and after getting off to a 13-25 start in 1925, Breadon fired Rickey and replaced him as field manager with Hornsby. Breadon kept a disappointed Rickey on as business manager (read GM) and told Rickey he'd thank him for it one day. And so Rickey turned his attention to his ever-growing farm system and finding talent to fill the major league roster.

It paid dividends almost immediately. They won their first pennant in 1926, and beat the Yankees in a memorable World Series when the ancient Pete Alexander - who Rickey had picked up on waivers in mid-season - tossed a pair of complete game victories to win the second and sixth games. In the seventh game, old Pete stumbled out of the bullpen in the seventh inning with the Cards holding a 3-2 lead, to strike out Tony Lazzeri with the bases loaded. That game ended when Babe Ruth, representing the tying run, was thrown out trying to steal second with Bob Meusel at the plate and Lou Gehrig on deck. The Cardinals were world champions, and Rickey's network of minor league teams would keep the talent flowing for the next twenty years and more, well beyond his own tenure with the club. They won pennants in 1928 and 1930 and picked up their second championship in 1931 when Pepper Martin rapped out a series record 12 hits and drove the A's mad on the basepaths. Three years later, the storied Gas House Gang - yes, I've recounted

the saga of the Gas House Gang on these virtual pages - brought St.Louis a third title. Rickey left for Brooklyn in 1942, but the system he had assembled kept humming along in his absence, as they won three more championships in the 1940s. From 1921 through 1953, St. Louis had just three losing seasons in 33.

But Sam Breadon's health had begun to fail in the late 1940s, and he began looking for a successor who would keep the team in St.Louis. That eventually turned out to be Gussie Busch and the Anheuser-Busch beer company. Busch wasn't nearly as clever a baseball man as he thought he was. He put Trader Frank Lane in charge of his team. This did not go well. Lane traded away Bill Virdon, coming off a Rookie of the Year season, after a bad

month. Lane unloaded his fine second baseman, Red Schoendienst. Only when Lane tried to trade Stan Musial to the Phillies did Busch cry "Enough" and install local boy Bing Devine as his GM. Devine gradually assembled the team that would win three pennants and two WS titles in 1the 1960s, although Devine himself wasn't around to enjoy any of it, having been dismissed by Busch just before the good times started rolling. It's

a tale I've told before, as some of you may remember.

At this point, I'm going to assume you all have some familiarity of the Cardinals' fortunes over the last few decades - the Whitey Herzog years (three pennants, one championship), the hard times under Joe Torre, and their long recent run of success under Tony LaRussa (three pennants, two championships) - so I can turn my attention to the players. The Cardinals adopted uniform numbers in 1932, and seeing as they were generally awful for most of the period before that, we're going to catch all but a couple of their all-time greats in our net.

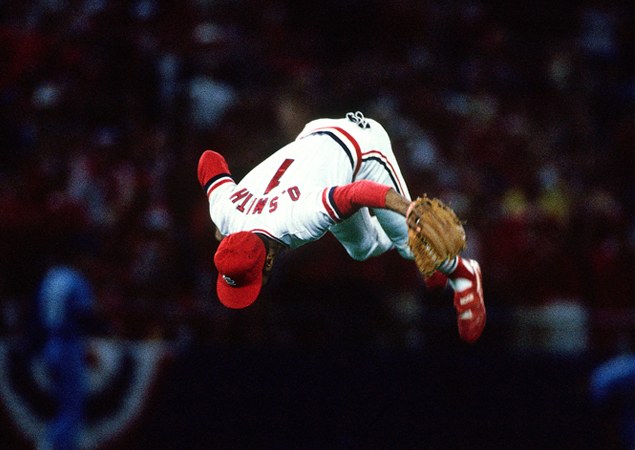

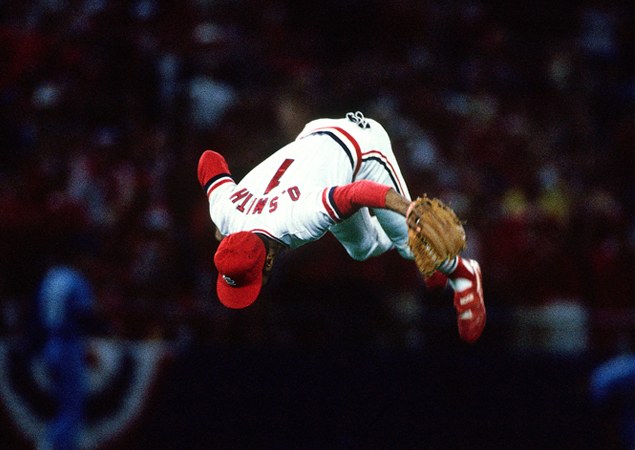

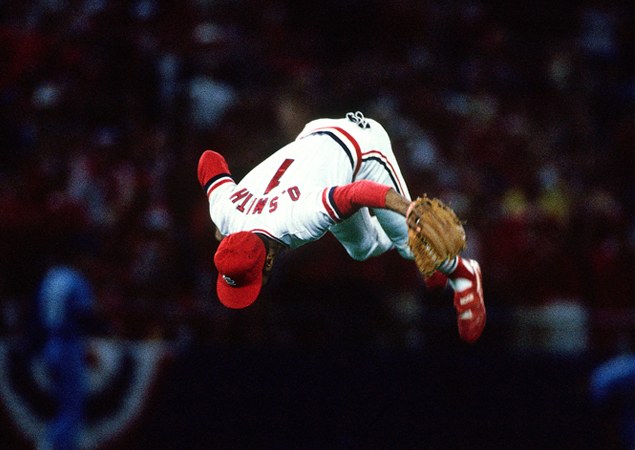

1 The hero of the 1931 World Series, the Wild Horse of the Osage, Pepper Martin wore this number for five seasons. Martin was a crude Okie version of Keith Moon, with his taste for smoke bombs and destroying hotel rooms. This number was also worn by Whitey Kurowski, third baseman for the great 1940s teams. Kurowski nearly lost his right arm as a child to osteomyelitis - the surgeries that saved his arm actually left it several inches shorter than his left arm. He underwent more than ten additional surgeries during his career so he could continue playing, but it eventually brought his career to an effective end before he turned 30. But there's a Hall of Famer in our midst, and there's a pretty good case to be made that Ozzie Smith was the greatest defensive player who ever lived. Omar Vizquel, who gets compared to him quite a bit these days, was a very fine shortstop himself but trust me, folks - Omar couldn't carry Ozzie's glove. No one could. Like Brooks Robinson, Smith's arm wasn't particularly impressive, but like Robinson he more than made it up for it with the accuracy of his throws and the quickness of his release. The fact that groundballs got to Smith much more quickly on the artificial turf he played so many of his games on also helped mitigate the ordinariness of his arm. You see, Ozzie Smith could get his hands on pretty well any ball hit between the third baseman and the second baseman. He just could. He was an amazing athlete, with the grace and balance of a great dancer - watching him play was like watching Baryshnikov play shortstop. He wasn't a black hole with the bat either (Ozzie was also a better hitter than Vizquel? Yup.). Smith had no power whatsoever, but he never struck out, drew more than his share of walks, and was a terrific base stealer. It's my view that the 1987 NL MVP vote, when Ozzie finished second to Andre Dawson, was even worse than the AL result the same year.

2. We occasionally find, in some of these old franchises, someone who after a long career as a player remains with the organization, often in uniform, for decades afterwards - Frank Crosetti in New York, Johnny Pesky in Boston, Jim Davenport in San Francisco. In St. Louis, that man would be Red Schoendienst who appeared in 19 seasons as a Cardinal player, and spent almost another fifty years wearing the team uniform as a coach and manager. It almost never happened, any of it. He suffered a serious injury to his left eye as a teenager - he nearly lost the eye and his vision in it was never the same. He learned to switch hit to compensate and it worked. He had more than 2400 hits in the major leagues and played in 10 all-star games. He won a championship with the 1946 Cardinals, and after Frankie Lane traded him away, he helped Milwaukee win the 1957 title. Tuberculosis almost ended his career, but he fought his way back to finish his playing days with the Cardinals as a backup infielder, pinch-hitter, and playing coach. He took over as the manager when Johnny Keane resigned, and led the team to two more pennants and a WS title in 1967. His ten year run as manager ended in 1976, but Whitey Herzog brought him back to the Cardinals as an interim manager in 1980 and then as one of Herzog's coaches. He remained with the organization until the day he died, by which time he had become the oldest living Hall of Famer and last man alive who played in the 1946 World Series.

3. The Cardinals won their first championship in 1926, with Rogers Hornsby managing the team. Hornsby - a man whose life revolved around baseball and betting on horses, only one of which activities he was good at - thought this achievement warranted a raise. The Cardinals, a notoriously skinflint organization in those days, begged to differ. So they traded him to the Giants, for New York's second baseman, the Fordham Flash Frank Frisch. John McGraw had seen a lot of himself in the young Frisch. Naturally, after a few years together, they couldn't stand the sight of one another. Frisch was no Hornsby - not that there has ever been anyone remotely like Hornsby - but he was a hell of a player in his own right. He was basically the Roberto Alomar of his day, a switch-hitting line drive hitter, a fast and aggressive baserunner, an alert and hustling defender. He was the NL MVP in 1931, when the Cardinals won their second title and three years later, by then a player-manager, he'd manage the Gas House Gang to their championship in 1934. His later work in St. Louis, Pittsburgh and Chicago would prove that he really wasn't much of a manager at all, but he always talked a great game. In his old age, he ended up on the Hall of Fame Veterans Committee, and by sheer force of personality he managed to get an ungodly number of his old teammates through the gates of Cooperstown and into the Hall of Fame - Travis Jackson, Fred Lindstrom, Dave Bancroft, Jesse Haines, George Kelly.

4. How good a shortstop was Marty Marion? Batting seventh for the first place Cardinals in 1944, Marion hit .267/.324/.362 and was named the NL's Most Valuable Player. Marion was the first shortstop to win an MVP, and he's still the only man to win the award almost entirely with his glove. His own teammate, right fielder Stan Musial, had hit .347/.440/.549 so this was perhaps a peculiar vote but it does tell you how Marion's defense was regarded by the people who watched him play. And infield defense was much more important in the 1940s than it is today. Back then, the defense had to come up with 24 outs per game. Nowadays, they only need to find 18 of them. But we have to pass Marion by for a contemporary star. The greatest catcher in franchise history is either Ted Simmons, just voted into the Hall of Fame, or Yadier Molina who will likely follow him to Cooperstown. Eventually. Yadier can't approach Simmons as a hitter but he was by far the better defensive players - he didn't collect nine Gold Gloves by accident - and in his best years was a fine complementary bat as well.

5. I assume you're pretty familiar with Albert Pujols who spent eleven seasons in St. Louis laying waste to NL pitching. I'll just point out that Albert the Great also won a slash line Triple Crown, in 2009. I know, Hornsby did it seven times. But even once is pretty impressive.

6. "When we're children we can believe that baseball players are heroes, people to look up to and admire without reservation. We all grow up, we all learn otherwise. But Stan Musial never let me down." That's what I wrote upon Musial's passing back in January 2013. It was an emotional moment for me and I just might have put my hard-earned cynicism away for a split-second there. But Stan Musial was that kind of man. He lived more than 90 years and he never let anyone down. Thomas went on to express his regret at never having seen him play. Well, I'm so old I actually did see Stan Musial play baseball (not that I have anything like a true memory of it) and strangely enough - I don't think you missed much. There has surely never been so great a player who had less flash than Musial. Aside from his extremely odd batting stance, there was little that was memorable or distinctive about him. He worked hard at his craft and he ran out every ground ball. He had 1815 hits in his home games and 1815 hits on the road because... that's what he was like. He didn't hit tape measure home runs. He didn't run like the wind. He didn't make spectacular plays in the field. He didn't even have a regular position. He was forever moving around to accommodate the team's needs. He played LF as a rookie, moved to RF for two years, missed a year in the Navy, came back and played two years at 1B, spent two years split between RF and CF, split two years between LF and 1B, then spent a year in CF, a year in LF, a year at 1B, a year in RF, two years playing 1b and RF, three years mostly at 1B, and finished with three years in LF. He always just said hey, whatever you need, and banged out another 200 line drives. He didn't have a big personality. He didn't boast of his achievements. He was a cheerful, friendly man, who was always grateful for his good fortune. He liked meeting people and he loved to play the harmonica. There was nothing really distinctive about him at all - nothing except his relentless, undeniable, overwhelming greatness. Year after year after year after year. All the bold black ink on his bb-ref.com page just has to speak for itself. Which it does, loud and clear. He was the greatest Cardinal of them all, one of the greatest players to ever step on a baseball field.

7. His nickname wasn't "Ducky" - it was "Ducky Wucky" and as you can probably imagine, Joe Medwick absolutely hated it. Which meant that anyone who used it within his earshot was asking for a whole lot of trouble. Medwick was a notoriously fiery competitor and overall hothead, who famously helped provoke a near riot in the final game of the 1934 World Series. He fought with umpires, he fought with opponents, he fought with teammates, and he really fought with Sam Breadon over the size of his pay cheque. He arrived in St.Louis September 1932, just 20 years old, and started hitting immediately. He was an impatient line-drive hitter, who didn't hit a lot home runs but he hit for some very high averages while bashing out an obscene number of doubles. He hit 64 of them 1936, a figure that has been surpassed exactly once in the game's long history (by Earl Webb in 1931.) His bat didn't age well - he had an OPS of .911 in his 20s, and .749 in his 30s and was finished by age 36. He'd worn out his welcome in St.Louis long before that happened. Rickey had traded him away in 1940 for four warm bodies and $125,000. A week later, batting against the Cardinals for his new team, his former teammate Bob Bowman drilled him. In the head. Bowman, Medwick, and Dodgers manager Leo Durocher had evidently had some kind of confrontation in the hotel lobby the night before. Medwick spent four days in hospital before being released. He immediately suited up and knocked out a couple of hits.

8. The acknowledged leader of the great 1940s teams was centre fielder Terry Moore, who played all eleven of his major league seasons with the Cardinals.He arrived in 1935, and didn't hit much at first, but he was a wonder in the outfield from day one. He may have been the fastest man in the National League, and he put that speed to use in the field. He was a fearless and aggressive defender. After a few years in the league, he added some muscle to his skinny frame, became a productive hitter as well, and played in four All-Star games. The Cardinals won the World Series in 1942, Moore's eighth season - and he spent three years in the army. When he got out, he was 34, he'd lost a step, his bat had regressed and he was done after three more seasons. But for a few years there, he was pretty special.

9. How many players are mostly remembered for a single play? In Boston and St.Louis, the name Enos Slaughter always means his mad dash home with the winning run in the final game of the 1946 World Series. They tell the tale to this day - how Boston shortstop Johnny Pesky held the ball as Slaughter scored from first on a single. Let's get the story right. Slaughter was on first, but he was running on the pitch. Harry Walker's hit wasn't a single - it was a double to left-centre. And Pesky barely hesitated with the relay - he turned, saw Slaughter flying around third, and threw home immediately. It just wasn't in time. Slaughter is in the Hall of Fame, which is a little like putting Bill Buckner or Johnny Damon in the Hall. But he was a good player. He was a corner outfielder with little home run power, but he hit for average, lined doubles and triples, and drew lots of walks.

10. The Cardinals retired the number for Tony LaRussa, one of two men to manage the Cardinals to a pair of WS titles (the other was Billy Southworth) but the Big Cat, Johnny Mize, is one of the game's forgotten greats. We've seen some great first baseman over the years, from Gehrig and Foxx to Pujols and Bagwell. Johnny Mize is right there with them, one of the ten best ever. The war had a big impact on the shape of his career, costing Mize three full seasons, but he picked up right where he'd left off when he came back. He missed out on the St. Louis championship teams of the early 1940s because - in one of the more head-scratching moves in franchise history - the Cardinals had traded him to the Giants after the 1941 season. What did they receive in exchange for one of the most fearsome sluggers in the game, in the heart of his prime? They gpt a backup catcher, a backup first baseman, and a back of the rotation starter. Oh yes, and $50,000 too, which was probably the point of the whole transaction. In his six years as a Cardinal, Mize had hit .336/.419/.600 with 158 HRs. He'd led the NL in homers twice, in slugging three times; and he'd lead the NL in HRs two more times after getting out of the navy. He finally began showing signs of age in 1949, so the Giants sold him to the Yankees that August. Finally, he got to play in a World Series, for a winner, and he would spend his final four seasons in the Bronx as part of Stengel's first base platoon. Which means he got to be part of four more championship teams. It took a mysteriously long time for the Veterans Committee to put him in the Hall of Fame, but I suppose they had to deal with George Kelly and Travis Jackson first. They did finally get around to Mize in 1981 so he got to enjoy it for a dozen years.

11. The ace of the 1946 champs was a skinny southpaw named Howie Pollet, whose career was interrupted once by war and repeatedly by shoulder problems. He still managed a couple of 20 win seasons and led the NL in ERA twice.

12. In 1959, the Giants brought Willie McCovey to the majors. The year before, they had graduated Orlando Cepeda, and two years earlier their system had produced Bill White. So if you were wondering just where all those outstanding National League first basemen of the 1960s came from... now you know. White was doing military service in 1957 and 1958 when Cepeda burst onto the scene and seized the first base job so the Giants traded him to the Cardinals for Sad Sam Jones. Obviously as a hitter White wasn't the equal of Cepeda, whose first five seasons or so are basically a match for Henry Aaron. Nor could he compare with McCovey, who was probably the most fearsome hitter alive in the 1960s. But White was certainly a quality hitter in his own right, he was much more durable than either Cepeda or McCovey, and he also provided an elite glove at first base where the others often struggled to achieve mere competence. (That's once the Cardinals figured out that they were better off with Musial in left field and White at first base - they did it the other way around in his first year with the team.)

13. You know about Matt Carpenter, heading into his tenth season, looking for a bounce-back year. This was also worn by Mort Cooper, the 1942 MVP, who posted three successive 20 wins seasons during the war years.

14. When you win an MVP award when you're not having your best season, you're probably a pretty good player. Ken Boyer wasn't quite the equal of his brother Clete with the glove, but Ken was a good enough defender at third base to win five Gold Gloves himself. The Boyer brothers each hit a home run in the final game of the 1964 World Series, the only time that's ever happened. Ken was by far the more dangerous hitter. Over his seven year peak, age 27 to 33, he hit .303/.372/.500 while winning his Gold Gloves. He won his MVP when he drove in a league leading 119 runs for the 1964 champs, but any of his seasons from 1959 through 1961 can match that performance. He got started a little late - he did two years of military service before coming to the majors - but he stayed good enough long enough to play in 11 All-Star Games.

15.For some strange reason, the National League was awash with LH hitting catchers in the 1960s: Ed Bailey, John Roseboro, Smokey Burgess, Tom Haller, Clay Dalrymple all playing regularly, while guys like Jesse Gonder, Carl Sawatzki and Vic Roznovsky also saw action. Burgess and Bailey were the best hitters, Roseboro and Edwards were the best defenders but Haller and Tim McCarver of the Cardinals were the most complete players. McCarver eventually played in four decades, thanks to token appearances in 1959 (at age 17!!) and 1980. But as fine a player as McCarver was, Jim Edmonds was better. He was a good player for the Angels in his 20s, but upon coming to St.Louis at age 30 he took a great leap forward. He gave the Cards six tremendous seasons in succession, hitting .292/.406/.584 and earning a Gold Glove each season. His Hall of Fame ballot was one and done, which is hard to fathom. He did get off to a late start - that, and all the walks he drew took a bite out of his counting numbers. He also got no respect whatsoever from the MVP voters. In 2003, he won yet another Gold Glove while hitting .275/.385/.617 - and finished 27th in the voting. Okay, he wasn't going to take the award away from Barry Bonds. But 27th?

16. Jesse Haines is in the Hall of Fame, and while I don't think he was anywhere near the quality one expects of a Hall of Famer he was certainly a fine pitcher. He won 210 games over 18 seasons with St. Louis and only Bob Gibson won more games in a Cardinal uniform..But Ray Lankford, whose career was recent enough that many of you should remember him pretty well, was a better player.

17 They don't make them like Dizzy Dean anymore. It's probably just as well. It must have been exhausting dealing with him all the time, however charming and entertaining he could be. There was a great deal of ol' Diz in young Muhammad Ali - the braggadocio, the flashing wit, the delight in his own wonderfulness, the sheer sense of fun that simply emanated from him. Racism and war, his religious calling, all the social pressures of his time sent Ali's life in a another direction. Dean was always free to just be Diz. Asked to account for his success, he explained that "I was blessed with a strong arm and a weak mind." He may have had but a second grade education but Dizzy was never anybody's fool. He was a born entertainer, a natural public speaker who could entertain any crowd for hours at the drop of a hat, while never letting mere facts get in the way of a good story. He was born Jerome Herman Dean... or was it Jay Hanna Dean.... in 1910... or was it 1911? Who knew? And what did it really matter? As Diz explained, all these reporters had come asking him questions and he wanted to give each one an exclusive. As a ballplayer - well, he was the Sandy Koufax of the 1930s, a blazing meteor that flashed through the skies and was gone. He was a great pitcher. As everyone knows, a line drive off the bat of Earl Averill in the 1937 All-Star Game fractured his toe. ("Fractured? Hell, the damn thing's broke" Dizzy exclaimed.) He was back on the mound three weeks later trying to pitch through it, and permanently damaged his arm. He was 27 years old, with a 133-68 lifetime record. His raw strikeout numbers don't look all that impressive by today's standards, but the 1930s was a low strikeout era and Lefty Grove's K numbers don't look that impressive either. Dean only pitched five full seasons, but he led the NL in Ks four straight years, and was second the other time. He led the league in wins twice, and in saves once. In the final week of the 1934 season, with the Cardinals locked in a desperate struggle with the Giants for the pennant, Diz pitched a complete game to beat the Pirates on Tuesday. On two days rest, he shut out the Reds on Friday to pull the Cardinals into a tie for first place, and on a single day's rest he tossed yet another shutout against the Reds on Sunday to clinch the pennant. When his playing days were over, he moved smoothly into broadcasting and spent decades delighting America with his unique way of describing the action. Here's George Metkovich stealing a base: "That Moklovich, he slud into second and howdja like ta have ten guys named Moklovich on your team?" When outraged schoolteachers complained about the language habits the children of America were learning from him, Diz fired back "you learn 'em English and I'll learn 'em baseball."They don't make them like that anymore. No sir. After Dizzy Dean they broke the damn mold.

18. We all know outfield to third base conversions seldom work, but the Cardinals made it work with Mike Shannon. He took over in right field in 1964 and had the best year of his life in 1966. After the season, the Cardinals traded third baseman Charley Smith to the Yankees for Roger Maris. While his power would absolutely disappear in Busch Stadium, Maris was still a fine outfielder. The Cardinals clearly made this move with the idea of moving Shannon to third base, although he'd never played an inning there in his life. But it worked. Shannon fought the position to a draw for three seasons before kidney disease ended his career at age 30. He moved into the Cardinals' radio booth shortly afterwards, and now 80 years old, is still working their home games.

19. Go figure. If we look at this number for the Blue Jays - we start with one of the very few men to win HR titles in both leagues, a guy who finished his career with the same number of career homers as Lou Freaking Gehrig. But we pass him over for a World Series MVP, a Hall of Famer with more than 3,000 career hits. But then we make way for one of the greatest Blue Jays of them all, the man who flipped his bat. Quite the collection. So what can the Cardinals, with their long and glorious history, offer? Well, how about Tom Pagnozzi? Seriously? Sure. Pagnozzi spent his entire 12 year career with the Cardinals, serving mostly as the backup catcher although he did get in a couple of seasons as the main guy. He didn't give you much with the bat, but he was a good defender. Look, it's him or Jon Jay.

20. The Chicago Cubs did many weird things in the 1960s - the College of Coaches, anyone? - and several of them involved their fine young outfield prospect, Lou Brock. They had signed him out of Southern University and Brock had torn up the Northern League, batting .361 with 38 stolen bases. So the Cubs made him their centre fielder. The 1961 Northern League was roughly equivalent to A ball today, so they were expecting quite the leap in just his second pro season. When Lou batted just .263 the Cubs were simply dismayed. They also couldn't fathom how a player so fast could be such a bad outfielder. So, despite the fact that Lou's arm was always well below average, they tried him in right field in 1963. The Cubs. What can I say, except once more, they were disappointed. So they just gave up and traded him to St. Louis in June 1964, in what history now records as one of the worst trades ever made. The Cardinals weren't too worried about Brock's outfield play - they had the great Curt Flood patrolling centre field. They stuck Brock in left field and told him to just go out and hit. And run. Which he did, and he didn't stop until he'd hit and run his way into the Hall of Fame. By the time he was done, he'd set the single season and career records for stolen bases, cleared 3,000 hits, and helped his team to three pennants and two championships. He was the great World Series performer of the 1960s and one of the greatest of all time - in his 21 WS games, he hit .391/.424/.655, stole 14 bases, and scored 16 runs.

21. This was worn by Dizzy Dean's kid brother Paul, who came up at age 21 and gave the Cardinals two very fine seasons before his arm gave out. But

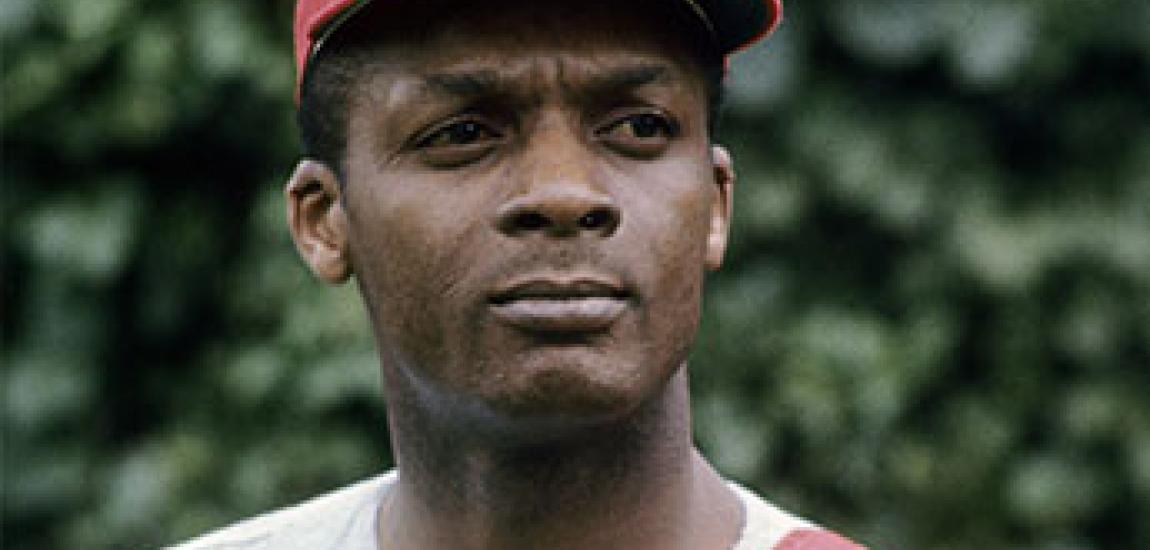

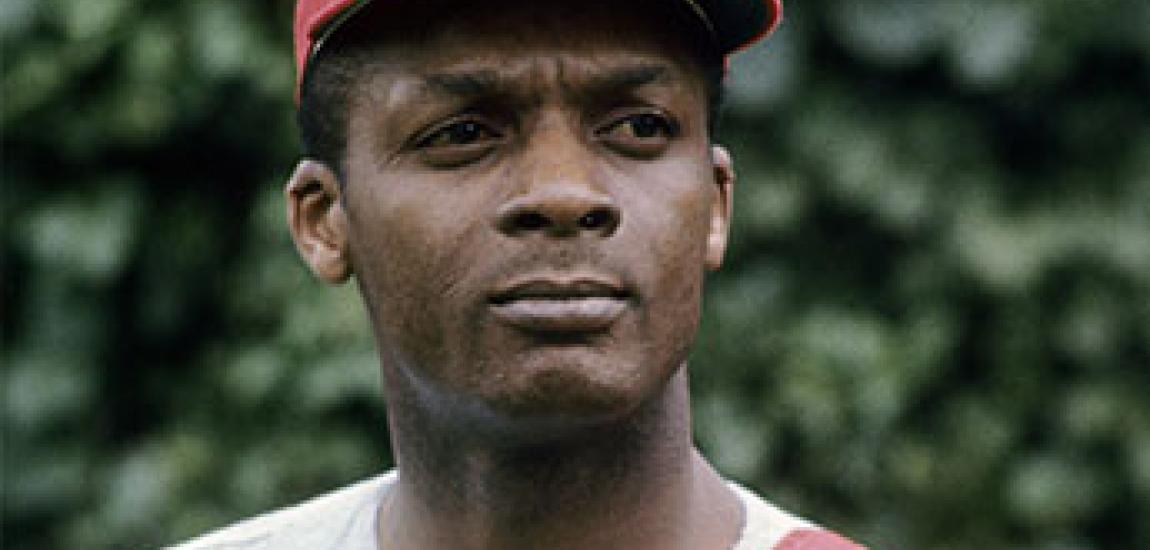

Curt Flood is a significant figure in the game's history, so significant that the player has been largely forgotten. He was a good one. He was the best defensive centrefielder in the National League once Willie Mays moved into his mid 30s. He was mostly a singles hitter who didn't take a lot of walks, but he generally hit enough singles to make an offensive contribution as well. But we remember him today primarily for his challenge to the reserve clause after being traded in 1969. It's sometimes forgotten that Flood's challenge failed. It went all the way to the Supreme Court, which ruled on behalf of the owners. Flood had sacrificed his career in a losing clause. But his legal challenge brought into focus the nature of the system that deprived players of their most basic human rights. He was vindicated by the Seitz decision in 1975 that nullified the reserve clause.

"I do not feel I am a piece of property to be bought and sold irrespective of my wishes. I believe that any system which produces that result violates my basic rights as a citizen..."

22. Nicknames, Bill James once observed, turned nasty in the 1930s. Bill Hallahan wasn't known as Wild Bill because of his lifestyle or his personality. He was Wild Bill because no one knew where the ball was going after he threw it. And Wild Bill threw very, very hard. He led the NL in walks three times - he also led the league in wins once and Ks twice. He pitched in four different World Series for the Cardinals (he went 3-1, 1.36) and was part of three championship teams. He was a scrawny little left-hander with big ears - his mother couldn't do anything about the ears, but she tried for years to cure him of his left-handedness. If his control had been better...well, they couldn't have called him Dumbo but they'd have come up with something in that vein.

23. It was Ted Simmons' misfortune to come aboard just as the great Cardinals teams of the 1960s were getting old and sliding out of contention. They finished second three times in his first four seasons, but were never in contention again. When Whitey Herzog took over the team in 1980, he decided he didn't like Simmons' defense and asked him to switch positions. Simmons didn't want to move - he liked catching - and Herzog being Herzog, Simmons was on the next plane out of town, to Milwaukee as it happened. Like Mike Piazza, Simmons was almost certainly a better defensive player than his reputation suggests (although by the time Herzog arrived on the scene, it may well have been time for him to switch positions.) But he was active in the same league at the same time as Johnny Bench, his arm didn't impress anyone and he never developed a reputation as a handler of pitchers. The fact that the Cardinals in the 1970s seldom had any pitchers worth handling was generally overlooked. As a hitter, however, Simmons was simply one of the best at his position in the history of the game, every bit Bench's equal and much more consistent from year to year..

24. Dick Groat won an MVP with the 1960 Pirates and he was the runner-up in 1963, the first of his three years in St.Louis. He wasn't normally anywhere near that good a player, and we do have a Hall of Famer we can talk about. The White Rat, Whitey Herzog took over the St.Louis job after being run out of Kansas City. He would manage the Cardinals to three pennants in the 1980s and win one WS title, in 1982. Herzog was one of the great managers of his generation. Like Earl Weaver, he didn't worry too much about what players couldn't do. He didn't try to make anyone into something he wasn't. His focus was always on what a particular player could do that would help the team win. He built a team that suited the park they played in - lightning fast artificial turf and outfield fences that were just a rumour in the distance. Herzog also made Weaver look like a sentimental old softie. He always knew exactly what he wanted, he had complete faith in his own judgement, he tolerated no half-measures, and was absolutely fearless. He had run John Mayberry out of Kansas City over his drug abuse, and been fired for it. In St. Louis, he got rid of franchise icon and pillar of the community Ted Simmons when he wouldn't change positions, traded budding superstar Garry Templeton because he didn't like his approach to the game, and followed that up by trading his MVP first baseman, Keith Hernandez, for ten cents on the dollar. Every one of those had crossed him, each in his own way and that was more than enough. Whitey Herzog ran his team his way. End of discussion.

25. I was tempted to go with Julian Javier, the slick second baseman on those great 1960s teams, or maybe even Silent George Hendrick, who was what passed for a slugger on Herzog's early 1980s teams. But I guess we have to go with Mark McGwire. His achievements in St. Louis all seem tainted now, but everybody let it happen. And cheered wildly at the time.

26. You probably remember

Kyle Lohse. It wasn't that long ago. He wandered the majors for sixteen seasons, pitched for six different teams, but had his three best seasons in St.Louis.

27. You definitely remember Scott Rolen. He was a Cardinal for parts of six seasons, and gave them both the best (2004) and the worst (his injury-plagued 2005) years of his Hall of Fame career. (They haven't voted him in yet? They will. They have to.) Rolen was about as fine a third baseman (non-Brooks Robinson division) as I've ever seen, and an astonishing athlete for someone so freaking huge. This number was also worn by Dal Maxvil, the light-hitting defensive whiz manning shortstop for the 1960s teams.

28. Tom Herr was the second baseman on those fine 1980s teams. In 1985 he had one of his better seasons, hitting .302/.379/.416 with 8 HRs. And, batting third behind Vince Coleman and Willie McGee, he had 110 RBIs. One of those things...

29. You will all remember Chris Carpenter, as well. The one who got away.

30. Orlando Cepeda had an MVP season, won two pennants and played for a WS winner in St. Louis. Even so, he had his best years as a Giant and spent more time in Atlanta. So around 1980, the Red Sox came up with not one, not two, but three quality LH starters - John Tudor, Bob Ojeda, Bruce Hurst. Then as now the Red Sox played their home games in Fenway Park, about the least hospitable environment a southpaw could hope to find, in this life or the next. While all three gave the Red Sox some quality seasons, all three eventually found their way to National League teams and a much happier existence. The Red Sox traded Ojeda to the Mets for a package that included Calvin Schiraldi. Ojeda promptly won 18 games for the 1986 Mets and came back to haunt the Sox in the World series (so did Schiraldi, now that I think of it.) They hung on to Hurst the longest, but he eventually lit out for San Diego as a free agent. Tudor was already long gone, having been traded to Pittsburgh in 1984. The Pirates sent him on to the Cardinals. A year later, at the end of May 1985, Tudor was sitting pretty with a 1-7 record for his new team. He hadn't been pitching all that badly however and as the calendar turned to June he suddenly became unhittable and unbeatable. Over the final four months, Tudor went (read this carefully) 20-1, 1.37. He threw ten shutouts - only one man in the last 50 years can match that (Palmer in 1975) and the last man to top it was Bob Gibson himself in 1968. Tudor wasn't striking out many people, but in Busch Stadium in the 1980s, you didn't need to. He never gave up a home run (it was Busch Stadium in the 1980s) and he never walked anyone. So if they hit the ball on the ground Ozzie Smith gobbled it up and if they hit it in the air one of the speed merchants in the outfield would track it down. It worked. He was never that effective again, but he remained a fine pitcher for a few more years until arm miseries gradually ground him down.

31. We have to slight a couple of pretty good pitchers here. Only Bob Gibson started more games for the Cardinals than Bob Forsch, and only Gibson and Jesse Haines won more games in the uniform. And in 1960, the Cardinals picked up the old Whiz Kid, Curt Simmons off the scrap heap after he'd been released by the Phillies. Simmons reinvented himself as a finesse pitcher and gave the Cardinals a couple of very fine seasons, going 18-9 for the 1964 champs. But Harry Brecheen was the greatest LH pitcher in team history (well, they traded Steve Carlton.) Harry the Cat was already 28 years old before he won his place in the St.Louis rotation. Branch Rickey always liked big guys who could throw hard, and his Cardinals had no shortage of that type of pitcher. So they kept sending Brecheen down to Columbus. Brecheen went 16-9, 16-6, 19-10 for Columbus from 1940 to 1942. If it hadn't been for the war thinning the St.Louis rotation (and Rickey leaving for Brooklyn) Brecheen might have never gotten his chance. But once he finally got hold of a big league opportunity, he didn't let go. He spent seven outstanding years in the rotation (105-59, 2.74, ERA+ of 139). He was 34 years old by then, thanks to his late start, but he closed his career gracefully with four more effective years as a swingman. He was easily the star of the 1946 World Series - he tossed a pair of complete game victories, one of them a shutout, and then came out of the bullpen to win the finale as well.

32. He's best remembered as a Phillie, of course, but Steve Carlton had his first great season as a Cardinal. He had his first 20 win season in St. Louis, and he won his first WS title there. These are three different seasons we're referring to, and we've still got to take into account another season as a Cardinal when he made the All-Star team. He went 14-9 in his first full season in the majors, for the 1967 champs. He was an All-Star in both 1968 and 1969, and the latter season was especially impressive - 17-11, 2.17. After an off-year in 1970, he bounced back with a 20-9 campaign and another All-Star appearance in 1971. He was 26 years old. The following spring, the Cardinals traded him, for Rick Wise. Why? Because Gussie Busch was angry with him for holding out. For an extra $5,000. The whole thing was entirely typical of both men. Gussie Busch made many, many bad baseball decisions. And Steve Carlton was as stubborn and inflexible as any man could be.

33. The pride of Maple Ridge, Larry Walker, finished his Hall of Fame - yes! - career in St. Louis. But Walker played just 144 games as a Cardinal and only one player in the history of the game has been known as "Vinegar Bend." Wilmer Mizell was actually born and raised in Leakesville Mississippi, but for some reason his family collected their mail at the post office in Vinegar Bend, across the state line in Alabama. (Why Vinegar Bend? - apparently some time past a train had derailed in the area, spilling its load of, yes, vinegar.) Mizell was a country boy (how country? he really was throwing barefoot when checked out by a Cardinals scout), a big, hard-throwing left-hander who struggled with his control. Man, there have surely been hundreds of this type of player over the years. Mizell was always wild, but he honed his control by throwing rocks at squirrels. He spent six pretty good years in the Cardinals rotation, despite losing two full seasons to military service, and in 1960 they traded him to the Pirates in one of those trades that worked out wonderfully for both clubs. The Cardinals received Julian Javier, who obviously had no future in Pittsburgh (two word - Bill Mazeroski, who was just 23 years old), and Javier would spend the next 12 years at second base for the Cardinals. And Mizell would go 13-5, 3.12 and help the Pirates to their first championship in 35 years..

34. Nelson Briles was a good one, who went 14-5 for the 1967 champs and won 19 games to help the Cards to a pennant the following season. But I actually think Danny Cox was just a little bit better, although his pitching motion was always a shoulder injury just waiting to happen.

35. Back in 2010, the Cardinals were battling the Reds for first place in the Central and decided they needed some pitching help. So they worked out a three way deal with Cleveland and San Diego. St.Louis sent the Padres, themselves battling the Giants in the NL West but indesperate need of help in the outfield, Ryan Ludwick, their right fielder. The Padres sent out a couple of pitching prospects, one to St. Louis and one to Cleveland, and the Cardinals ended up with Jake Westbrook from the Indians. Well, it didn't work out for anyone - St. Louis and San Diego both ended up in second place - but it worked out especially badly for the Padres. First, Ludwick completely stopped hitting as soon as he arrived in San Diego. And the prospect the Padres sent to Cleveland? That would have been Corey Kluber. Oops. Westbrook pitched well enough for the Cards but our man has to be Matt Morris, who spent eight years in the Cardinals rotation and won 101 games for them.

36. Many pitchers have been inconsistent from one year to the next but John Denny brought out new dimensions of the whole concept of inconsistency. At this juncture, it looks like he was worked so hard in his good years that fell apart (and consequently pitched much less) the following year. It's as if he had to pitch badly to pitch well. And vice versa.

37. While Andrelton Simmons might someday make me question Ozzie Smith's place as the greatest defensive shortstop ever, nothing has ever made me doubt that Keith Hernandez was the best defensive first baseman I have ever seen, the best I ever hope to see. He was one of those corner infielders, like Brooks or Olerud, who couldn't run at all. That simply doesn't seem to matter when your first step is that quick and your anticipation is that superior. Hernandez was one of the very few defensive players I've ever seen who somehow made it seem like he was the one who was on offense when he was in the field. (Clemente was another.) He always seemed to be one step ahead of everybody else. He was also a very fine hitter - his power was less than what we expect from first basemen (season high just 18 HRs) - but he did everything else with the bat that you'd want instead - lots of doubles, lots of walks, lots of hits. He had his last complete season at age 33 - a hamstring injury wiped him out for almost two months in 1988 and a broken kneecap in 1989 finished him off. Given better health at the back end of his career, his counting numbers would have helped him at least stay on the Hall of Fame ballot longer than he did. But he gave us a great Seinfeld episode and a couple of baseball books that are actually worth reading.

38. Bruce Sutter left as a free agent after the 1984 season but the Cardinals were getting by just fine with Jeff Lahti and Ken Dayley splitting the closer duties between them. But earlier that year in Louisville, the Cards' first round draft pick from 1982, after almost four years of making little progress as a starter, had been switched to a relief role and immediately started tearing the American Association apart. This was Todd Worrell, and the Cardinals brought him to the majors, just in time to be eligible for the post-season. He won 3 games and saved 5 down the stretch, and pitched well in the post-season (a mysterious safe call by Don Denkinger messed up his final appearance.) Worrell opened the following season as the team's closer, saved 36 games with a 2.08 ERA, and was the NL's Rookie of the Year. He pitched well for three more seasons before losing two full years to injury. After not pitching at all in 1990 and 1991, he made his way back to the Cardinals - who had brought in Lee Smith to replace him - and had an outstanding year (much better than Smith's, in fact) as a setup man. He then went to the Dodgers as a free agent, struggled through two ineffective and injury-plagued years before once more emerging as an elite closer.

39. Several interesting pitchers donned this jersey number for the Cardinals, and I'll want to mention them all. The best of the bunch was Larry Jackson, who spent six quality years in the St.Louis rotation before going to the Cubs in the Don Cardwell trade (the Cards then flipped Cardwell to the Pirates for Dick Groat.) Jackson almost won 200 games (he ended up with 194) in his career. He almost won a Cy Young when he won 24 games for the 1964 Cubs (there was only one award between the two leagues back then, and it went to Dean Chance of the Angels.) When his playing days were done, he was almost elected governor of Idaho (well, not really - he finished fourth in the Republican primary.) Jackson's number was then assigned to the only man from the University of Toronto to play in the majors, and that's my alma mater, folks - of course I'm going to talk about him. Our man, as you have probably surmised, was the long time Blue Jay team doctor, Toronto's own Ron Taylor. The doctor was only with the Cardinals for two years and change - he actually had his best years with the Mets - but he was part of World Series championships with both teams. He made two appearances in both the 1964 and 1969 series, working a total of 7 innings and he still hasn't allowed a World Series hit. Finally, at the beginning of the 1970s, a left-hander with a huge mustache donned this jersey. Al Hrabosky dubbed himself the Mad Hungarian and he snorted and stomped around on the mound like a crazy person, hoping it would frighten the hitters. He had one sensational season out of the Cardinals pen and a bunch of decent ones. Finally, it was passed to Bob Tewksbury, a soft-tossing RH starter who didn't give up home runs and didn't walk anybody. He spent five years in the St.Louis rotation, and his best season would have been 1992, when he went 16-5, 2.16 while walking 20 batters in 233 IP.

40. The Cardinals have been in the habit of giving this jersey to fine pitchers who spent most of their careers elsewhere but managed to spend a year or two in St. Louis along the way - Troy Percival, Rick Sutcliffe, Dan Quisenberry, Pete Vuckovich, Sonny Siebert, Rick Wise. The one with the most significant tour as a Cardinal would have been Andy Benes, who managed to win 155 games in the majors while somehow being regarded as a disappointment all along. Benes was one of the most hyped pitching prospects of his day. He was drafted first overall by the Padrees in 1988. He spent just four months in the minors. By August 1989 he was pitching, and pitching very well indeed in the major league rotation. That's where he'd be for the next fourteen seasons. He did two tours with tthe Cardinals and had his biggest season there (18-10 in 1996). Benes was always a good pitcher, a solid mid-rotation guy for many years. It's just that he was supposed to be a star.

41. Bad timing, that's all. Lindy McDaniel appeared in 21 major league seasons. He pitched for the Cardinals in the 1960s, and then for the Yankees and Royals in the 1970s. And somehow he never got to throw a pitch in the post-season because none of his teams made it there. It wasn't his fault. He was one of the first great career relief pitchers, all of whom emerged in the National League in the 1950s. Those pitchers were all worked much, much harder than anyone would dream of working a reliever today, and the hard throwers all broke down pretty quickly. The ones who lasted were the soft-tossers with a trick pitch, like Roy Face and Hoyt Wilhelm, and McDaniel who was something in between - he was a sinker-curveball guy, who later on added a forkball. He spent a couple of years working mostly as a starter for the Cardinals before finding his true calling and leading the National League in saves three times, twice as a Cardinal. Not that anyone was actually keeping track back then. McDaniel was (and is) a deeply conservative, devoutly religious man of great personal dignity - kind of an Okie Mariano Rivera - which sometimes made for an odd fit in a major league clubhouse.

42. Here is a tale of two pitchers, whose careers overlap. The first man was active from 1976 through 1988 and the second from 1982 through 1995. One is in the Hall of Fame, and one isn't.

ERA G GF SV IP H R ER HR BB IBB SO HBP BF ERA+ FIP WHIP H9 HR9 BB9 SO9 SO/W

2.83 661 512 300 1042 879 370 328 77 309 83 861 13 4251 136 2.94 1.14 7.6 0.7 2.7 7.4 2.79

2.67 642 548 311 789.2 607 252 234 64 255 29 861 9 3194 157 2.72 1.09 6.9 0.7 2.9 9.8 3.38

The top line belongs to Bruce Sutter, indeed a significant pitcher in the game's history. Sutter was voted in by the writers in 2006. The second line belongs to Tom Henke, who had received 6 votes and instantly slipped off the ballot five years earlier. Don't get me started...

43. Ken Hill came up with the Cardinals, but he didn't begin to harness his tools until he went to Montreal. Dennis Eckersley actually spent a couple of years with the Cardinals, and saved 66 games for his old boss LaRussa. But he wasn't really The Eck anymore, as his 1-11, 3.58 mark as a Cardinal might suggest. So let's go with a southpaw, Joe Hoerner, whom the Cardinals stole from Houston in the Rule 5 draft in 1965. Hoerner had four very fine seasons in the St. Louis bullpen before being traded, along with Tim McCarver and - wait for it - Curt Flood, to the Phillies in the Dick Allen deal. Hoerner likewise gave the Phillies four very fine seasons before closing his career as a wandering LOOGY (five teams, six seasons, more appearances than innings pitched.)

44. A serious shoulder injury took much of the heat away from his fastball and much of the shine off his prospect status but Ray Washburn battled back to pitch a no-hitter and help the Cards win a title.

45.

I've written at length about

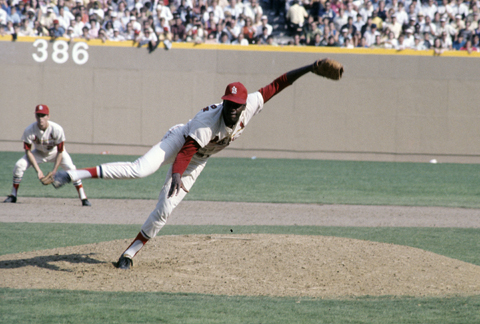

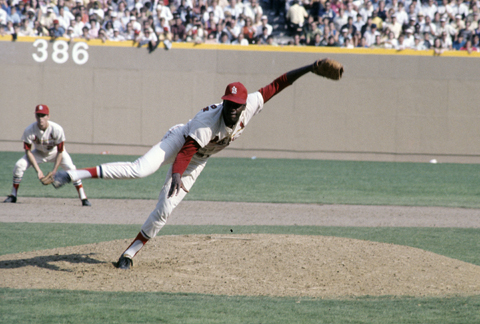

Bob Gibson before - no one who saw him play will ever forget him - and there's little I can add except to wish him the best. He was hard to describe, but I did my best. Take Rivera's cutter, Stieb's slider, and Halladay's sinker. Imagine absolute command and control of this fearsome repertoire. Imagine a superior athlete, good enough at another sport to go to college on a scholarship. And no one ever talked about these things because they were simply struck dumb by how ferociously competitive he was, an impression only magnified by his distinctive way of delivering the ball, which seemed to involve

leaping at the poor hitter with bad intent. Yeah, he was unforgettable. Get well, Gibby.

46. He may have been the worst free agent signing in Blue Jays history. It wasn't his fault. Ken Dayley was supposed to be a star. The Braves drafted him third overall in 1980 out of the University of Portland, but like a lot of young southpaws it took him a few years to gain control of the strike zone and the Braves had traded him to St.Louis by the time he did. Whitey Herzog made him a reliever and he had six fine seasons in the St.Louis pen. His Cardinal tenure included about as fast a recovery from Tommy John surgery I've ever heard of (he was hurt in July 1986 and he was back for spring training the following February) as well as an impressive post-season streak of 15 consecutive scoreless appearances before finally allowing a run (on a Kent Hrbek homer, with the bases full of Bob Forsch''s baserunners, in a one-run game.) He signed with the Blue Jays as a free agent for the 1991 season - and suddenly was unable to play. He'd come down with vertigo, and nothing was able to solve the problem. He pitched just 5 innings with the Jays and his career was over. It's now thought possible that a bout with meningitis in 1987 may have brought on his issues. Dayley battles with his vertigo to his day, but has since learned ways to avoid its onset and cope with it more readily.

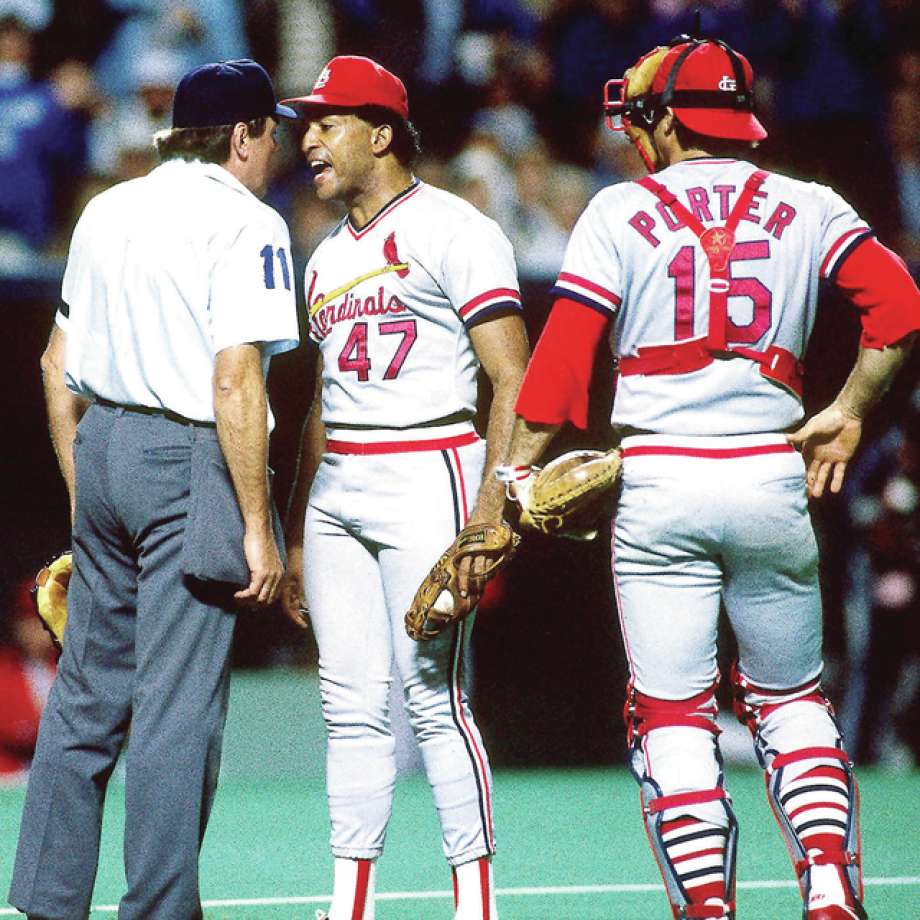

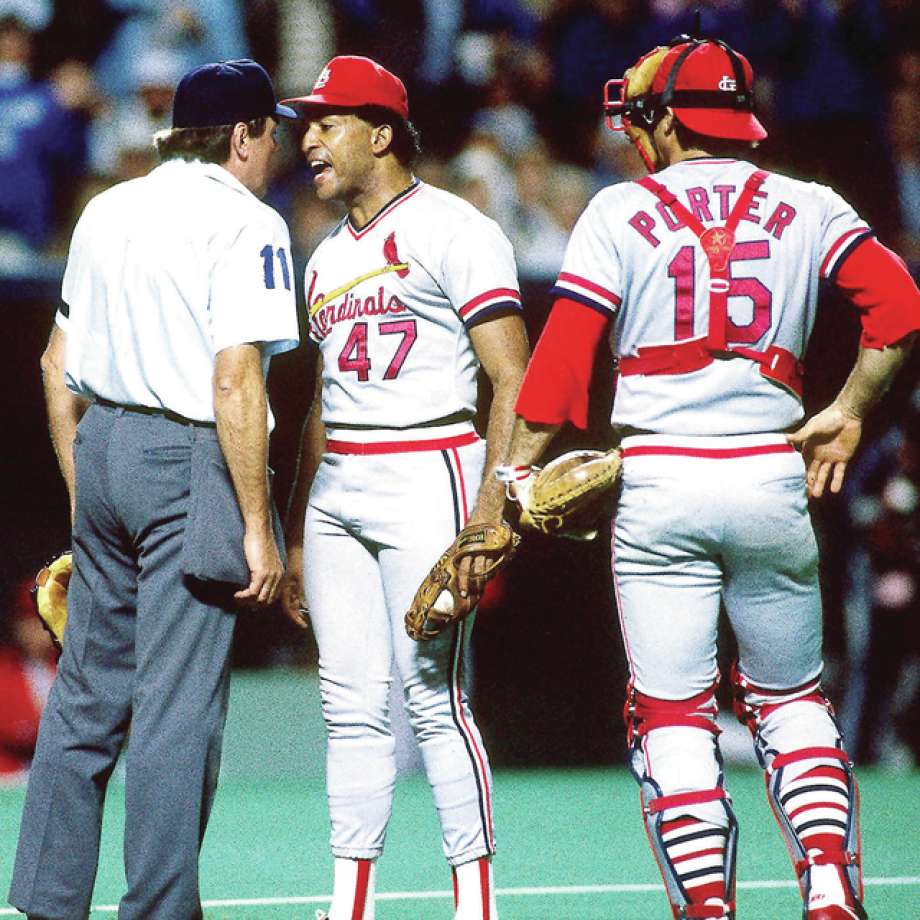

47. "My favourite word in English, and I love this word, is 'youneverknow'. For this contribution to the game's accumulated wisdom Joaquin Andujar will surely be remembered forever, and fondly too. Andujar was yet another player from the baseball factory of San Pedro de Macoris, who spent five seasons in Houston, and went to two All-Star games. But the Astros couldn't quite figure out what to do with him. They ran him back and forth between the rotation and the bullpen. Which Andujar did not appreciate, and Joaquin was not the kind of man to keep his opinions to himself. Finally, they traded him to St.Louis and Whitey Herzog quickly figured out what made Andujar tick. "He's a pleasure to deal with. He just goes crazy when he's not pitching." Herzog made him his workhorse for the next four years, pitching him on three days rest whenever possible and slotting his other starters around him. He went 15-10 for the 1982 champs and beat the Brewers twice in the World Series. After a bad year in 1983, he bounced back with 20 win seasons in 1984 and 1985. The Cardinals traded him to Oakland at that point and he had one decent year with the A's before he began to fade. He was one tough Dominican.

48. The first thing that came to mind when I saw the name Mike Torrez was the pitch that hit Dickie Thon in the face in April 1984. Thon was just emerging as one of the best players in the game, and he never came close to being the same player again. This was a seismic event - it's not Carl Mays and Ray Chapman but a great young player's career was permanently altered, which means it had an impact on the next ten National League pennant races. And then I remembered - geez, it was Mike Torrez who threw the pitch to Bucky Dent in the 1978 playoff game, which was hit for one of the most famous home runs in the history of the game. Was it a hanging slider? Or was a spitball? And then I remembered - geez, it was Mike Torrez who threw the pitch that ended the 1977 World Series, with a popup to himself on the mound, in the same game when Reggie hit his three home runs on three pitches. Torrez beat the Dodgers twice in that World Series, which ended the Yankees unimaginably long championship drought. Torrez then had the cheek to sign with the Red Sox as a free agent. Well, he'd just finished working for George Steinbrenner and Billy Martin. After working for Charlie Finley. After pitching for Earl Weaver. After pitching for Gene Mauch. I imagine Don Zimmer seemed positively restful at that point. The man's long career was not exactly without incident, and it all began in St. Louis. He won 185 games along the way. What a long strange trip it was.

49. Slim pickings here. Ricky Horton was a LH who had several fine seasons working mostly out of Herzog's bullpen in the late 1980s. They either traded him just in time or he was just no good once he left Busch Stadium.

50. Tom Henke wore this number as he closed his outstanding career by saving 36 games with a 1.82 ERA for the 1995 Cardinals. Meanwhile, Duane Ward was retiring just 6 of the 25 batters he faced in his futile comeback attempt after missing all of 1994. Clearly I'm never getting over the Jays forcing Henke to walk. It's just not going to happen. Luckily, we can change the subject and acknowledge a career Cardinal, long-time ace Adam Wainwright. I trust you know all about him and his curveball.Just this past year, he fought back from serious injury for the third time to go 14-10 and then provide some outstanding work in the post-season. He's won 20 twice, 19 twice, been a Cy Young runner-up twice, and third place finisher twice.

51. The Yankees used to be run by fools who did dumb things on a regular basis. Good times! In 1981 they traded a young outfielder named Willie McGee to the Cardinals for a LH named Bob Sykes, who'd gone 23-26, 4.65 in his undistinguished career. Those would be his final career numbers, as he never pitched in the majors again. The Cardinals put McGee in centrefield and he never looked back. McGee was a skinny switch-hitter with blazing speed and no power. He didn't take a walk, but he could hit for average (he led the NL twice) and he was perfectly suited to covering the vast outfield expanse in Busch Stadium. He played 18 seasons in the majors, rapped out 2,254 hits and won the the 1985 MVP award when he hit .353.

52. I imagine you're familiar with Michael Wacha, who's been a fixture in the St.Louis rotation these last few years.

53. Pitching is bad for you. Greg Mathews was a promising young RH who won 11 games for the Cardinals in 1986 and again in 1987. But he hurt his arm the following year and didn't make it back until 1990, when he went 0-5, 5.33. The Cardinals released him, Kansas City gave him a look but cut him loose. He caught on with the Brewers and spent 1991 in their minor league system before getting released again. He made his last major league appearances with the 1992 Phillies before calling it quits at age 30.

54. Blue Jays fans don't have warm and fuzzy memories of Jaime Garcia, but he was a fine starter (62-45, 3.79) for the Cardinals for several years. He just wasn't much use to anybody else.

55. LaRussa always liked guys who could play many of positions, and with Skip Schumaker, he more or less invented one. He came to the majors as an outfielder, but in spring 2009 LaRussa released his incumbent second baseman and installed Schumaker there. He'd never played the position before, but he held down the spot for a couple of years before evolving into an all-over-the diamond kind of guy. He did that job for a couple of years in St.Louis, and filled the same role as his career wound in Los Angeles and Cincinnati.

No one particularly memorable has worn the numbers beyond 55 for the Cardinals, with the exception of #57. That was the number worn by the unfortunate Darryl Kile who, upon being liberated from Colorado, posted 20 and 16 win seasons in St.Louis. And then, just 33 years old, he died in his sleep one afternoon of an undiagnosed heart problem. Before they put numbers on the jerseys, Cy Young and Kid Nichols, two of the greatest pitchers at the turn of the previous century, both spent two years in St.Louis, though they built most of their legends elsewhere. Bill Sherdel was a fine pitcher for those good 1920s teams, even if he did lose all four of his World Series starts. Jim Bottomley and Chick Hafey both spent most of their Hall of Fame careers with the Cardinals, although I'm not sure either of them was quite that good. And Rogers Hornsby towers above them all.

25 comments

https://www.battersbox.ca/article.php?story=20200117234610338