Lobby of Numbers: Chicago Cubs

Monday, May 10 2021 @ 07:00 AM EDT

Contributed by: Magpie

The National League was founded in February 1876, and Chicago provided one of the charter franchises, coming over from the National Association of Base Ball Players which had provided a very loose organizational structure for the preceding five years.

It was a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away.

Ulysses S. Grant was the president of the United States. It was the nation's centennial. It was also an election year. Out west, army columns under the command of Alfred Terry were searching for the wild Lakota. After refusing to sell the Black Hills to the US government, they had been ordered to report to a reservation. They were not inclined to comply, and were gathering in unprecedented numbers, somewhere out there. The Seventh Cavalry was out west looking for them, and George Custer was desperate to join his regiment. Alas, he was stuck in DC, testifying in the Belknap case. He badly wanted to whip Sitting Bull and those pesky Sioux, cover himself,in glory, and return to Washington in triumph. Hopefully he could get all this done by the 4th of July. And then, who knows? Maybe the grateful Democrats would nominate him for president. A fellow can dream, after all.

By April, the National League teams were ready to play ball. On the 25th, Chicago's team beat the Louisville Grays 4-0 in their first game, behind star pitcher Al Spalding (who would soon give up playing the game and go into the sporting goods business.) Chicago's National League franchise has had a winning record ever since. No other team can make this claim, that the overall franchise record has never fallen below .500 (there are three teams that have never been above .500, so let the guessing begin!)

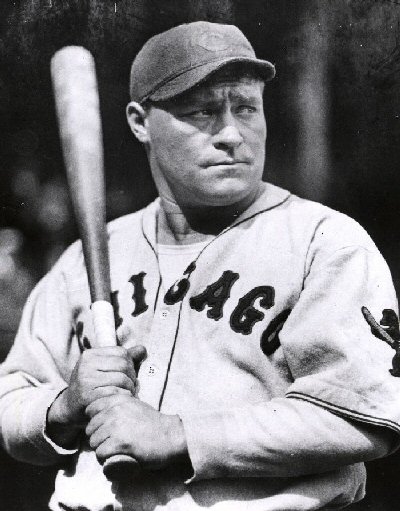

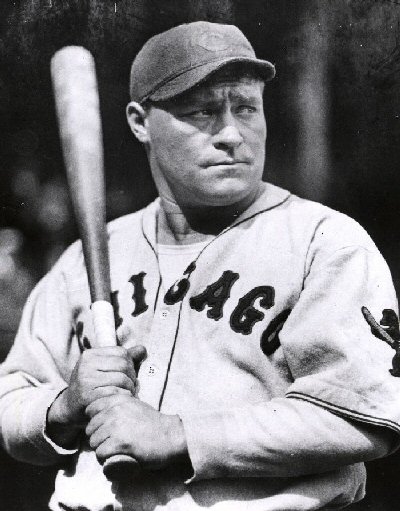

Cap Anson is the dominant figure in the team's 19th century history. By 1879, age 27, he was the team's manager, star hitter, and first baseman. He would hold all three of these positions until he was 45 years old. Anson still holds the franchise's records for hits, runs, and runs batted in although what with the vagaries of 19th century record keeping no one is quite sure what those actual numbers should be. Except that they certainly amount to more than anyone else ever did. Anson was a belligerent, quarrelsome man and his refusal to play against integrated teams helped drive players of colour out of the major leagues. But he was also celebrated, successful, and thought to be handsome. For better or worse, he was the game's first celebrity.

After beginning their life as the White Stockings, and playing as the Colts (1890-1897) and the Orphans (1898-1902), Chicago's National League team adopted the Cubs nickname in 1903. They were about to embark on what must still be regarded as the most dominant run by any baseball team in the game's history. This is not up for dispute. From 1904 through 1913, the Cubs played .645 ball. They won 986 games in that time - no team has won more games over ten seasons, despite the longer schedules that have been in place for more than half a century. (Those Cubs also won more games than any team in history over a two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, and nine year period.) But they made it to just four World Series during this decade of dominance, winning just twice. And their biggest stars, the men the team is remembered for, were their defenders. There's no impressive batting numbers (this was a pitcher's game - in 1907, the league averages were .243/.308/.309). There are no flashy video highlights to keep their memory alive, or to explain why they were so damn great. But they were.

I think it had something to do with the way talent was distributed at the beginning of the 20th century. There was simply a much greater variation in ability between the best players in the league and the worst, far greater than what you find today. The Cubs were great because their defenders were so much better than the other teams' defenders. You would not duplicate that today, even if you had Keith Hernandez at first, Mazeroski at second, Ozzie at short, and Brooks at third. You might have the greatest defenders ever at each position - but they wouldn't be that much better than the other guys around the league. Whereas the Cubs defenders really were that much better. They were good players and they knew what they were doing. They also had some new ideas about how to play defense, involving positioning and assignment of responsibilities, that would eventually be adopted everywhere. After all, John McGraw was watching them beat his team. McGraw paid attention, and he spent the next quarter century teaching the game.

That great Cubs team got old, as teams always do, and the Cubs scuffled for a while. They made it to the World Series in 1918 but lost in six games. That same year they were able to obtain the great Pete Alexander, whom the Phillies in an act of monumental cynicism, had placed on the market believing that he'd be drafted into military service. As indeed he was, and Alexander was a shattered ruin of a man when he returned from the war. He was a ruin who could still pitch, even as he sank deeper into alcoholism to help relieve the psychic and physical torment he carried with him. But the team didn't win anything until they did one of the smartest things any team has ever done. It was the Cubs who did it first. They hired Joe McCarthy.

McCarthy took over a losing team and in his first year as the manager they went 82-72. They improved their win total in each of the next three seasons and were back in the World Series by 1929. But they lost to the A's and were on their way to a disappointing 90-64 record when the Cubs one of the dumbest things any team has ever done. They fired Joe McCarthy. Even worse, they made their best player the manager. A fellow named Rogers Hornsby. It was team owner William Wrigley who did the insane deed, and team president William Veeck was so disturbed that he resigned on the spot, only to relent when Wrigley promised never to interfere again. (This was Veeck senior, by the way - his son is much more famous, and for good reason!)

Hornsby's reign of terror (Veeck's later description) lasted less than two years. Veeck replaced him with Charlie Grimm midway through the 1932 season. The Cubs made it to the World Series and the players voted Hornsby a zero share of the Series money. They made it back to play for championships again in 1935 and 1938. They lost each time, and they lost again in 1945. And then a long, long period of futility began. It would be 71 years before the Chicago Cubs would play once more in a World Series, and more than a century since they had last won one. Which means we need to to give it up for Theo Epstein, Breaker of Curses and Slayer of Ghosts.

The Cubs present an issue I haven't previously encountered, or at least not to such an extent. The Cubs adopted uniform numbers in 1932, and they were a very good team for most of that decade. You would expect them to be able to provide a number of representatives for our list below. You would be wrong. The problem is that the Cubs liked to change uniform numbers with great frequency during this period. Like, every year. Assigning a player to carry the banner for a particular number has often become a fairly random and sometimes quite arbitrary exercise. I'll often be going with Player A for some number even though he wore a different number more often - but I want to get Player B included somehow. Lon Warneke, for example, has to be here somewhere. He had three 20 win seasons for the Cubs in the 1930s. But he was wearing a different number every single time. (I'll expand on some of these weird dilemmas as they occur.)

And that's the situation in the 1930s, when they had good players. For most of the next seventy years, the team was usually pretty bad. So once more they were changing the player wearing that uniform number every year. It was just for a different reason.

It's a nightmare! But here we go!

1. It looks like the Cubs were following the Yankees lead when they assigned uniform numbers based on batting order position - it may explain why the numbers changed every year. But Woody English was the leadoff hitter and he stayed at the top of the order. He started out at shortstop but shifted over to third base when Billy Jurges arrived. English was playing third when Babe Ruth hit that famous homer in the 1932 series. English always maintained that Ruth did not call his shot. "Ruth would never have done that. Charlie Root would have murdered him if he did." English said he was holding up two fingers to tell the Cubs dugout that only had two strikes on him, that he still had one left.

2. Billy Herman followed English in the lineup and wore this number for five years, when it was adopted by star catcher Gabby Hartnett (who started out wearing 7.) But I've got another number available for both Herman and Hartnett, which frees this one up for Randy Jackson. He's completely forgotten today, but he was a solid third baseman for those awful Cubs teams of the early 1950s, and made it to a couple of All-Star games.

3. The third hitter on that 1932 team was Kiki Cuyler, who was beginning to show his age by this time, but was still a fine player. Cuyler was a line drive hitting outfielder, an outstanding base stealer, a centre fielder when he was young. In his best year, with the 1929 Cubs, he hit .360 - the following season he hit .355 while hitting ahead of Hack Wilson. Wilson drove in 191 runs and Cuyler scored 155 times. It might have been a bit of a stretch to put him in the Hall of Fame, but he did hit .321 lifetime and a late start (he didn't get going until he was 25) held down his counting numbers.

4. We're going to put Billy Herman here - he switched to this number in 1937 (even though he was still batting second) and kept it for the rest of his Cubs tenure. I'm afraid I've always mixed him up with Babe Herman, which is a little embarrassing. The two players had nothing in common except their names and a few years in Brooklyn. Babe Herman was a great hitter, but an utter disaster at all other aspects of the game. Billy Herman was just a really good ballplayer. He was the man who replaced Rogers Hornsby at second base for the Cubs and improved the team. He was the National League's best second baseman and a fine hitter as well. He played in eight All-Star games while helping the Cubs win three pennants and when they traded him to Brooklyn he helped them win the pennant and played in another couple of All-Star games. He's been in the Hall of Fame since 1975.

5. I'm going to put Billy Jurges here, mainly because I've got no one better. Jurges wore 11 when he came up, switched to 8 for a year, went back to 11, and finally wore this one during his last two years with the Cubs. That includes 1937, which was probably his best year anyway. Jurges wasn't a black hole at the plate but he was a below average hitter - it was his glove that kept him around to play more than 1500 games at shortstop in the major leagues.

6. One of the better players never to earn Hall of Fame induction was Stan Hack, who spent his entire sixteen-year career with the Cubs and whose name can generally be found in the top ten of most of the franchise's hitting marks. (The franchise is almost 150 years old, remember.) Hack was a left-handed leadoff hitter, a man who hit singles, drew lots of walks, and - naturally - scored lots of runs. He was also a very fine third baseman. He was certainly a better player than Pie Traynor (inducted in 1948) or George Kell (inducted in 1983.) He hit .348 in his four World Series appearances. It's a mystery. Well, Hack died a long time ago (in 1979) so maybe it doesn't matter all that much.

7. Rick Monday was a fine player for a very long time, and he gave the Cubs five good seasons in the midst of his career. He's remembered for being the first player chosen in the inaugural Major League draft back in 1965; for saving a flag about to be burned by protesters in the Dodger Stadium outfield; and for hitting a home run against Steve Rogers. When they say "Blue Monday" in Montreal... well, I don't want to rub it in. So let's acknowledge Jolly Cholly. Charlie Grimm spent eight years as the Cubs first baseman. Along the way, he replaced Rogers Hornsby as the manager and immediately took the team to the World Series. Grimm was a cheerful sort, an entertainer, a fun guy to be around. He was, in other words, the exact opposite of Rogers Hornsby. As a player, Grimm was an outstanding glove man who didn't hit that much for a first baseman. As a manager, Grimm gradually phased himself out as a player and moved into the dugout. The Cubs won another pennant in 1935, and in 1938 what had happened to Hornsby happened to Grimm. He was replaced as the manager by one of his own players (Gabby Hartnett) and the Cubs went to the World Series. Where they lost, yet again.

8. We have a couple of fine right fielders to choose from here. Bill Nicholson was the one who spent more time with the Cubs, but we'll meet up with him later on. We're going with the Hawk. Andre Dawson was a 32 year old outfielder who had been slowed by repeated injuries. He became a free agent after the 1986 season and no one even made him an offer (Collusion, kids.) Dawson badly wanted to get off the Montreal turf, and Wrigley Field looked nice. So he signed a blank contract with the Cubs (who filled in $500,000 in the salary line.) I was in a baseball pool that year, and I also thought Dawson would like Wrigley Field. He did, winning an MVP he didn't deserve and winning me some money I like to think I did deserve. The MVP award was a bad joke, but don't let that make you overlook the fact that Dawson played very well in Chicago for six seasons.

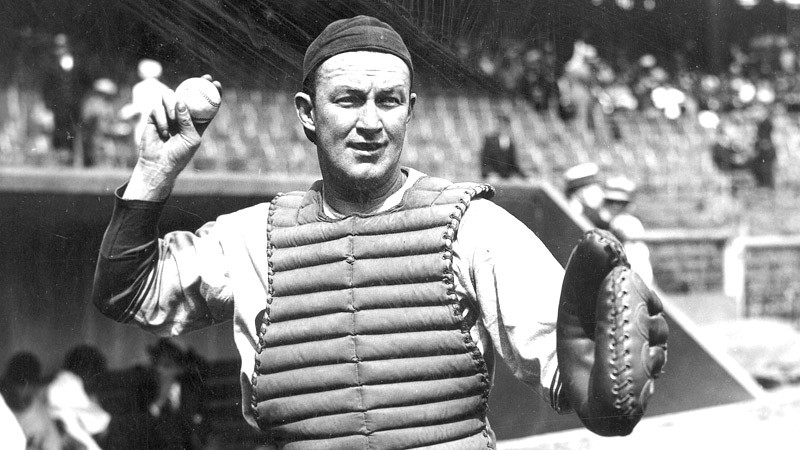

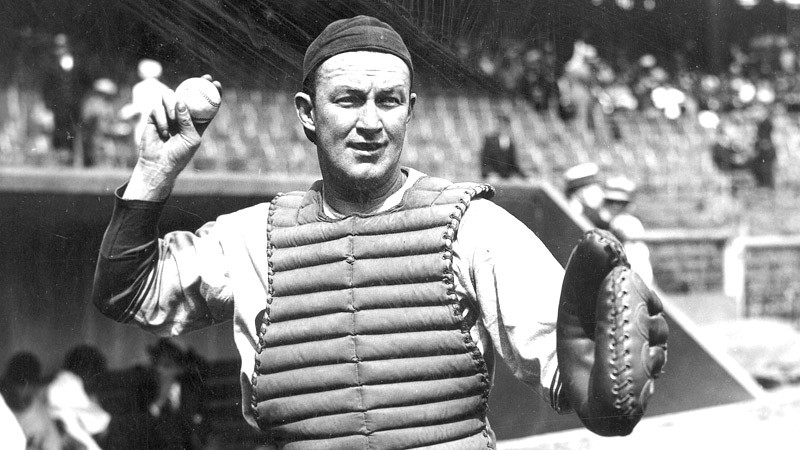

9. We're going to go with Gabby Hartnett in this spot, although he'd started out wearing 7 and had switched to 2 by the time he took over as the manager. He was known as Leo Hartnett when he arrived in Chicago in 1922, and he was so painfully shy that the local press, in their perverse way, dubbed him "Gabby." He would, in time, grow into the nickname, becoming one of the game's more notable chatterboxes. He was also the best catcher in the National League for most of his long career. He threw very well, handled the pitching staff nicely, and was a very good hitter. He was the MVP in 1935, and the runner-up two years later. His most celebrated moment came a year later. In the final week of the 1938 season, the Cubs were locked in a struggle with Pittsburgh for the NL pennant. The Pirates came into Wrigley leading by 1.5 games. The ghost of Dizzy Dean won the first game to cut the gap to one-half game. On Thursday afternoon, with the game tied 5-5 in the bottom of the ninth, Hartnett came up as the autumn darkness fell around the ball park. He hit a walk-off homer to end it. The "Homer in the Gloamin''" put the Cubs into first place - they finished the sweep the next day and met the Yankees in the World Series. Where they got smoked, of course. By the time Hartnett retired, he had caught more games than anyone in the game's history and still stands 15th on the all time list. It took an absurdly long time (ten years) for him to be voted into the Hall of Fame, but he crossed the bar in 1955. This number was also worn by another Cubs catcher, Randy Hundley. He came up as a 24 year old rookie and Leo Durocher had him catch 149, 152, 160, and 151 games in his first four seasons. I don't know why, maybe Hundley killed Leo's dog. And Hank Sauer was wearing this number when he quite unaccountably won the NL MVP award in 1952.

10. No disrespect to Leon (Bull) Durham, but one of the greatest Cubs who ever stepped on the field goes here. No Chicago Cub accumulated more WAR than Ron Santo (Cap Anson totalled more for the franchise, but Anson played for the White Stockings and the Colts.) Santo was an outstanding defender (five Gold Gloves) and a powerful offensive force. He was an intense player, a fierce competitor, not at all popular with opponents. He spent the prime of his career during the second Dead Ball era, but during those six seasons from 1963-68 Santo still hit .292/.379/.504 with 175 HR and 604 RBIs. What's especially remarkable is that he achieved all this while dealing with diabetes. Methods of monitoring one's blood sugar were not nearly as sophisticated in the 1960s - Santo sometimes found himself having to make his best guess as to his blood sugar levels and medicate himself accordingly. I suspect that this state of affairs had much to do with his career ending early, and it certainly contributed to his later health problems. He didn't complain. He never expected to live very long, and was happy and grateful for the time he was given. He spent some 20 years in the Cubs radio booth, waiting for the Hall of Fame to make a blindingly obvious call. He was one of the greatest third basemen who ever lived and it absolutely burns my ass that the Hall waited until he was gone, at age 70, before calling his name.

11. Having found some other place for Big Bill Lee, we have some shortstops. I've found another place to put Billy Jurges and Ivan de Jesus is best remembered for the trade that sent him out of town. Which leaves us Don Kessinger, the shortstop part of the Beckert-Kessinger double play combination for Durocher's 1960s teams. Kessinger didn't hit much at all, but his glove got him invited to six All-Star games and he ended up playing almost 2,000 games at short in the major leagues.

12. I think we're going to have put Lon Warneke here. He started out wearing 12 as he went 22-6, 2.37 for the 1932 pennant winners, leading the NL in Wins and ERA and finishing second (to Chuck Klein) in the MVP vote. He switched to 16 and won 18 and 22 games in 1933-34; finally he put on number 12 for his last two years as a Cub, winning 20 and 16 games, and going 2-0, 0.54 in the 1935 World Series. Then they traded him to the Cardinals for Ripper Collins and Roy Parmalee, both of whom were definitely past their prime. Warneke was a tall country boy with a good fastball and a big overhand curve, who won 192 games and went to five All-Star games. Others of note include Alfonso Soriano (I always forget he was a Cub, and a good one) and Shawon Dunston.

13. I suspect that the reason Claude Passeau blossomed as a fine pitcher after going from the Phillies to the Cubs had everything to do with the quality of the defenders behind him. He was a fully formed product by the time he made it to the majors at age 27. He truly looks to have been the same pitcher all along, striking out and walking the same number of hitters, allowing the same (minute) number of home runs. But he was generally allowing two fewer hits per 9 with Chicago's fine defenders behind him instead of the gang of bozos who played in Philadelphia. Passeau made four All-star games and went 124-94, 2.96 ERA in Chicago, after going 38-55, 4.15 as a Phil.

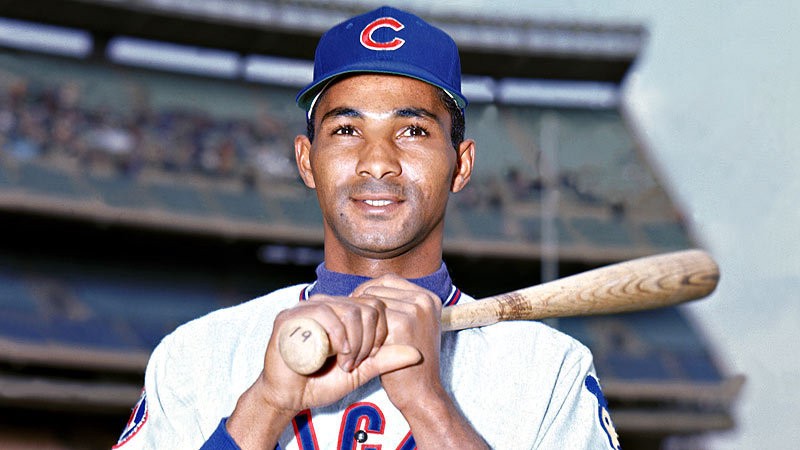

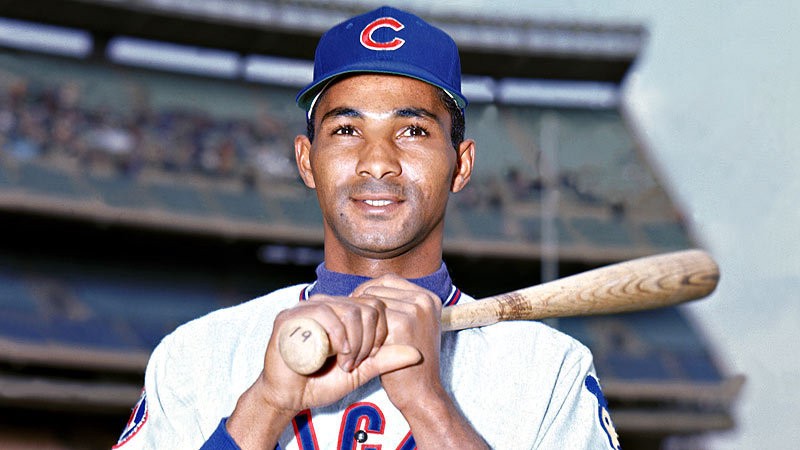

14. This is easy. Larry French was a fine pitcher but Ernie Banks was Mr Cub. He was a great, great player in the 1950s. I mean, you've got a Gold Glove shortstop who hits 40 HRs every year. What exactly do you want from a player? From 1955 through 1960, Banks hit .294/.359/.579, while averaging 41 HRs and 116 RBIs. His play declined sharply after that. The Cubs did many, many stupid things in the early 1960s (the College of Coaches!) - among them, they tried moving Banks to the outfield to make room for a non-hitting bonus baby at short. Banks hurt his knee crashing into the brick wall at Candelstick and it would bother him for the rest of his career. He had to move off shortstop, to first base. He was seriously beaned in 1962, he had mumps in 1963. He was in his mid 30s by now, just an ordinary player. And then Leo Durocher took over as manager. He would hold the job for the rest of Banks' career, and Durocher - unique among baseball men - disliked Ernie Banks. It's a shame that the last years of such an beloved and iconic player were such a misery. Well, Durocher was a creep. Ernie Banks started out in the Negro Leagues, playing ball for $7 a day. He went from there straight to the majors. He hit 512 HRs in the major leagues, won two MVP awards, and went into the Hall of Fame the instant his name appeared on the ballot. In his old age, he was given the Presidential Medal of Freedom, his nation's highest honour. The only thing he missed was seeing the Cubs win a championship, which they finally did 18 months after Banks passed on at age 83 in 2015.

15. If I don't put Bill Lee here, I'm going to end up with Darwin Barney or someone like that. This isn't the Spaceman - this Bill Lee was a big right-hander from Louisiana who went 106-70, 3.21 in his 20s and suddenly lost his effectiveness as he turned 30 (63-87, 3.95 for the rest of his career.) He was wearing this number in 1935-36, and he went 20-6, 18-11 those two years before switching to 11 for the rest of his Cubs tenure. He was the ace of the 1938 pennant winners, going 22-6, 2.66 - he led the league in Wins, ERA, and finished second (to Ernie Lombardi) in the MVP vote, exactly as Warneke had done six years before.

16. When he was 20 years old, Ken Hubbs was the NL Rookie of the Year. He was the first rookie to win a Gold Glove. And a little more than a year later, he had died in a plane crash. His teammates swore he was going to be a star - his Cubs hitting lines don't look like much, but his hitting had improved significantly in AA when he was 19. But the very next year he was in the majors. He'd been rushed through the system so quickly, and he was so very, very young. We'll never know. Lon Warneke wore this one for a while as well, but the best of the Cubs was clearly Aramis Ramirez. He'd come up with the Pirates and in his first full season at third base had hit .300/.350/.536 with 34 HRs and 112 RBIs. He was 23 years old. He had an off-year in 2002, but was bouncing back the following year when the Pirates dealt him and Kenny Lofton to the Cubs for shortstop Jose Hernandez. Hernandez was released five months later, while Ramirez settled in for a long run as a slugging third baseman - he hit .294/.356/.531 with 239 HRs in his 1124 games as a Cub. He finished up with 2,303 hits and 386 HRs - these are both outstanding figures for a career third baseman. He just got his first chance on the Hall of Fame ballot, and was an instant one and done. I don't think he was a Hall of Famer, and he wasn't a great defender, but he deserved a little more respect than that.

17. Apologies to Mark Grace, but Charlie Root has to go somewhere. He was a Cub for 16 seasons, and and after wearing three different numbers from 1932-34, he settled on this one for his final six seasons. Root is the only pitcher in franchise history to win 200 games as a Cub, something that's especially notable because he was already 27 years old before he got that first one. He is best remembered, of course, for a home run he allowed in the 1932 World Series. All the Cubs who were there seem to concur that if Root thought the Babe had called his shot, Root would have knocked him down the next time he came up to bat. (Of course, Gehrig followed Ruth with another homer, Root was hooked, and never faced Ruth again). Certainly no one - players, fans, media - said anything about it at the time. No one except one New York sportswriter (Joe Williams) who happened to be syndicated nationally. Video has been discovered, but it hasn't settled the issue. Ruth did make some sort of gesture. He certainly never pointed emphatically at the centre field bleachers, though he may have gestured in that direction. He might have been waving at the Cubs bench that he had one strike left. He might have been shooing a fly. It happened 89 years ago. I don't like our chances of ever knowing for sure.

18. The other half of the 1960s DP combination, Glenn Beckert, didn't do much with the bat either. He never struck out, but he never walked either, and he had no power whatsoever. What he could do was hit enough singles to post some respectable BAVGs. He was, however, a very fine second baseman and probably would have won more than a single Gold Glove if he hadn't been active at the same time as that Mazeroski fellow. A series of injuries ground his career to an early end.

19. This was Pat Tabler's number when he made his ML debut at second base for the 1981 Cubs. We've got a better second baseman than Tabby, though. Manny Trillo was a September callup for the Oakland A's in 1973, and he likely had a ringside seat for the nonsense that Dick Williams and Charley Finley perpetrated with the A's second baseman that year. He was traded to the Cubs a year later and settled in immediately at second base. He spent four years on the job for the Cubs and wandered around the league a bit. He probably had his best years with the Phillies. He didn't hit much but he won three Gold Gloves and made it to four All-Star games.

20. The Cubs acquired Adolfo Phillips in the 1966 deal with the Phillies that brought Ferguson Jenkins to the team. Phillips started out pretty nicely as well. The 24 year old from Panama took over in centre field and gave the Cubs very fine play in 1966 and 1967. But he was a sensitive and moody young man, unsure of his place in the game and in this new country. He'd found working for Gene Mauch an intolerable strain. Now he was working for Leo Durocher. Durocher, as was his wont, talked up Phillips' skills and then turned on him savagely when a scapegoat not named Durocher was required. He was back in the minors before he turned 30 and finished his pro career with three seasons in Mexico.

21. In the spring of 1992 the Cubs traded their left fielder, former Blue Jay George Bell, across town for a skinny young outfielder named Sammy Sosa. The old Dominican was just about done; the young one was just getting started. Sosa lost much of his first season on the north side of town to injury but then put together five fine seasons in a row, hitting at least 30 HRs four times. And by the time 1998 rolled around, he wasn't nearly as skinny as he used to be. I should think the rest of his story is pretty familiar. He ended hitting 545 HRs for the Cubs to set the franchise record.

22. The game's history is littered with countless what-if stories, most of them involving young pitchers who looked untouchable, unhittable - until they hurt their arms. Mark Prior of the Cubs is a famous recent example, and seventy years before Prior there was Dizzy Dean. The Cardinals unloaded Ol' Diz on the Cubs after he hurt his arm in 1937. He was 28 years old and a shadow of his old self. He appeared in just 13 games, and the man who had the NL in strikeouts four years running fanned just 22 batter in 74.2 IP. But working mostly with moxie and guile, he went 7-1, 1.81 anyway and started the second game of the World Series. He befuddled the mighty Yankees with slop and smarts and took a 3-2 lead into the eighth inning, when he was tagged for a two-out, two-run homer by light-hitting Frank Crosetti. Legend has it that as Crosetti rounded the bases, a frustrated Dean shouted that Crostti could never have done that two years earlier. And that Crosetti answered "I know." The lost greatness of Prior and Dean haunts the imagination. But it was lost. I suppose we really have to go with Bill Buckner here. He came up with the Dodgers, he achieved infamy with the Red Sox, but the Cubs got the best of him.

23. Two of the most lopsided trades in baseball history involved the Cubs robbing the Phillies blind, felonies so egregious that someone really should have done some time. A generation after the Ferguson Jenkins deal, the two teams swapped their light-hitting shortstops, Ivan de Jesus and Larry Bowa. But Bowa was 35 years old, and the Cubs got the Phillies to throw in a minor league prospect as a sweetener, a shortstop named Ryne Sandberg. Nice. He'd been a September call-up and the Phillies had used him exclusively as a pinch-runner and late inning defensive replacement. He spent his rookie year with the Cubs playing third base, but moved into the centre of the diamond the following year and immediately started carving out his legend. He went to 10 All-Star games, won 9 consecutive Gold Gloves at second base, and was the 1984 MVP. Phillies GM Paul ("The Pope") Owens blamed his scouts, claiming they had told him Sandberg would never amount to much more than a utility infielder.

24. The Cubs made some trades that didn't work out so great as well. Lou Brock wore this number during his three years with the Cubs, before they traded him away, so that he could become the greatest World Series performer of his time for the Cardinals. The Cardinals! As punishment for their sins, we're going to relive the Paul Minner era. Minner himself was actually pretty decent - he was a very tall, rather skinny LH whose grim task it was to pitch for the Cubs of the early 1950s. No man could possibly deserve such a fate, but that was Minner's. An injury in the minors had taken away his fastball before he ever made it to the majors, but he found a way to be effective with finesse and control. But the team was so, so bad - Minner went 6-17 one year with an ERA+ of 109. It's likely that he did something very evil in a previous life.

25. You should all remember Derrek Lee, it wasn't very long ago. He came up with the Marlins, helped them win the 2003 championship and was immediately traded to the Cubs. He fell off the HoF ballot immediately and I wonder if his fabulous 2005 season (.335/.418/.662 with 46 HRs and 107 RBIs) has made the rest of his career look a little disappointing. He was a very good player all along.

26. Even when I was a little wee boy, baseball people talked about guys with pretty swings. Just like today, those players were invariably LH batters. And the one I remember from that distant past was Billy Williams. It was pretty indeed, and it was pretty damn depressing if you had to get him out. He took over the Cubs LF job in 1961, when he was just 22 years old, and held it for thirteen seasons. It was downright boring how durable and consistent he was. He never had an off-year and he seldom missed a game. Every year - every single year - he hit at least .275, with at least 20 HRs and at least 84 RBIs. That was the floor, his bare minimum - his ceiling was a fair bit higher, all the way up to .333, up to 42 HRs, up to 129 RBIs. He was, and is, a quiet dignified man - he never caused any trouble, he never said anything memorable. He wasn't colourful at all. He just showed up every day and produced. Year after year after year. (Why gosh... he was the Fred McGriff of his day!) Williams went into the Hall in 1987, and the Cubs have retired his number. As is right and fitting.

27. Seeing as how I choose not to give Addison Russell the time of day, let's salute the original Vulture, Phil Regan. He picked up the nickname when he went 14-1 out of the Dodgers bullpen in 1966. He was traded to the Cubs in early 1968 and had four very effective years in the Chicago bullpen.

28. Coming to the Cubs with Regan was a journeyman outfielder named Jim Hickman, who'd started out playing five years with the hapless Mets. He had a little pop. But just a little. Then in 1970, he had a career year for the Cubs, hitting .315/.419/.582 with 32 HRs and 115 RBIs. He never approached those totals again.

29. Much to my surprise, the best choice here is my old favourite, the Crime Dog himself. Fred McGriff didn't want to be a Cub. He was happily playing out the back end of his career in his home town of Tampa. But the Cubs needed hitting and traded for McGriff just before the All-Star break. And McGriff refused to go, invoking his no-trade clause. He took an enormous amount of heat for this - doesn't he want to play in a World Series? Well, Fred McGriff had played in a couple of World Series, and played very well indeed as it happened. He had nothing to prove to anybody. He didn't need to chase a championship ring. He had one already, and he was happy at home. But after a few weeks, he relented and accepted the trade. He produced for the Cubs, as he'd produced for everyone - .282/.383/.559 with 12 HR and 41 RBI in 49 games. And he came back the following year and gave the Cubs the last of his ten 30 HR seasons.

30. The 1966 Cubs, Durocher's first team, were just awful. They went 59-103. They had a league average offense (not a good indicator for a Wrigley Field team) and they allowed more runs than any team in the majors. Even more than the Mets. Their best pitcher by far was a 20 year LH named Ken Holtzman, Holtzman and a relief pitcher named Jenkins who'd come over from the Phillies at the beginning of the season. Despite the 11-16, 3.79 record, Holtzman looked very promising indeed. He threw very hard and got his strikeouts; but he didn't walk people and he was hard to hit. And he was Jewish, which made him the next Sandy Koufax. Of course, it did. The following year, Jenkins moved into the rotation and posted the first of his 20 win seasons. Holtzman was called up to do six months of National Guard duty, and could only pitch during weekend passes. He made just 12 starts, but went 9-0, 2.53. The Cubs won 87 games. It was their best season since the 1945 team had gone to the World Series. Holtzman wasn't the next Sandy Koufax, of course. But he spent five more years with the Cubs, and did just fine with a couple of 17 win seasons. He was then traded to Oakland. He had his best years with the A's as part of that memorable rotation with Jim Hunter and Vida Blue that won three straight championships. But Holtzman suddenly lost his mojo, or at the very least his strikeout pitch, the moment he turned 30. Fortunately, he was able to get a five year deal out of George Steinbrenner before his decline became clear for everyone to see. There have been suggestions that Billy Martin didn't like Holtzman because he was Jewish, and refused to give him a fair shot. Hey, it's possible. It's Billy Martin, I'll believe just about anything. But I guarantee that Martin didn't like Holtzman because he was lousy. And sad to say, by then he was.

31. Well gosh. Two of the greatest right-handed pitchers who ever lived, both of whom won Cy Young awards as Cubs. Greg Maddux was one of my all-time favourites. He's one of those guys that the other players tell stories about, to this day. It's as if he was some kind of mythic creature. But we have to go with Ferguson Jenkins, who gave the Cubs a much bigger share of his greatness. This was the other case of robbery perpetrated on the Phillies - the Cubs acquired Jenkins and Adolfo Phillips from the Phils for two ancient starting pitchers, Bob Buhl and Larry Jackson. While Buhl was just about done, Jackson did give the Phillies three good years before retiring. But that's high price to pay for a Hall of Famer. After working out of the pen for a year, the Cubs put Jenkins in the rotation in 1967 and he ran off six straight 20 win seasons and took home the 1971 Cy Young. After a bit of a down year at age 30 in 1973, the Cubs traded him away to Texas. Where he won 25 games and another Cy Young. He made it back to Chicago in 1982, and went 14-15, 3.18 for a terrible (73-89) team at age 39. He finally ran out of gas the next year, just 16 wins short of 300. Which certainly wasn't going to keep him out of Cooperstown, where he belonged, and where he went in 1991.

32. History isn't fair. Don Drysdale went 209-166 in his career. He was a famous and celebrated star, and now he's a Hall of Famer. Milt Pappas, whose career largely overlaps with Drysdale's, went 209-164. He's the guy that came back to the Reds when their idiot GM traded Frank Freaking Robinson. Pappas really wasn't quite as good as Drysdale, but he was still a very fine pitcher for a very long time. He was the first man to win 200 games without ever winning 20 in a season; he's one of just 16 pitchers to win 150 games before turning 30 (only of them, Greg Maddux, would make it to 300 wins.)

33. Gene Mauch wasn't much of a player, and Bob Hendley is remembered, if at all, for a game he lost. Hendley was on the wrong end of Koufax's perfect game - Hendley pitched a one-hitter himself that night, and lost it on his catcher's throwing error. We do have Hank Wyse, who had several fine seasons for the Cubs and won 22 games for the 1945 pennant winners. Injuries ended his career soon afterwards.

34. Apologies to Kerry Wood, who was so overpowering he couldn't stay on the mound - but Jon Lester went 19-5, 2.44 for the 2016 Cubs, and followed that up by going 3-1, 2.02 in the post-season as the Cubs won their first championship in a century. That counts for a lot. He's won 191 games in the majors and he's been the top starter on two championship teams (and pitched on another.) And he isn't done yet.

35. Well, I like the guy's name. Even if he doesn't know how to spell it. And while my batch of the McIlroys are what's sometimes known as "Black Irish" (basically, we don't have red hair and freckles), you'd have to say Chuck McElroy was taking Black Irish to a whole new level. Folks, I have to say it: I don't think the man was really Irish, his name notwithstanding. I could be wrong. He was a LH reliever out of Texas, which is a good way to last for 13 seasons. He was pretty good, too. He pitched for nine different teams, but has his best, longest run with the Cubs.

36. Don "Every Day" Elston gave the Cubs some fine years in the bullpen. Mike Bielecki pitched for fourteen seasons. Only two of those were worth noting but they came while was with the Cubs, and his 18-7, 3.14 year helped lift that team to the post-season. But I think we have to go with Gary Matthews here. He came out of the Giants outfield factory of the early 1970s. He was the 1971 Rookie of the Year and eventually moved to Atlanta as a free agent. He was always a quality player, and played quite well when he finally got to Chicago in time for the 1984 post-season run.

37. Fluke seasons aren't all that common, for hitters or pitchers. Dick Ellsworth pitched in 13 major league seasons. In all but one of those years, he was a below average innings eater. He was a southpaw with good control, he generally kept the ball in the yard. He just gave up too many hits. Except in 1963, when he cut his hits allowed all the way down 6.9 per 9 - and went 22-10, 2.10 with an ERA+ of 167, which was better than Koufax (that's Sandy's 25-5, 1.88, 306 KS year.) Go figure. He never did anything remotely like that before or after.

38. You surely remember Carlos Zambrano - he was so fiery and colourful that it may have overshadowed what a fine pitcher he was. During his prime (2003-10) he went 111-64, 3.43 with an ERA+ of 130. He also batted .238/.248/.388 with 24 HR and 71 RBI in 693 at bats.

39. Generally, when the Cubs assign this number to someone that player's career takes a sudden turn for the worse. So let's salute Jason Hammel for stoutly resisting this trend, going 10-7 and 15-10 in his two Chicago seasons.

40. I don't remember actually watching The Rifleman - I may not be quite as old as I think - but I know it starred Chuck Connors. I also know that Connors played briefly for the Cubs in the early 1950s. Those Cubs were really bad, but not bad enough to keep Connors out of Hollywood. (Actually, maybe it was their badness that prompted him to light out for the coast.) Let's consider the 1984 Cubs. They had, typically, lost 91 games the year before. But they got off to a hot start in 1984, and in late May they sent for reinforcements. With Leon Durham far better to suited to first base than the outfield, the Cubs opened the spot for him by trading Bill Buckner. Billy Buck was sent to the Red Sox for Dennis Eckersley. Three weeks later, the Cubs sent a couple of outfield prospects (Joe Carter and Mel Hall) to the Indians for Rick Sutcliffe. These moves would have improved the team simply by getting Chuck Rainey and Dick Ruthven out of the rotation - the fact that Eckersley and Sutcliffe pitched so well improved the team so much that the Cubs quite unexpectedly won the NL East (where they ran into Steve Garvey, never a good idea at that time of year.) Sutcliffe in particular pitched so well (16-1, 2.69) that he won the Cy Young for less than four months work. Sutcliffe had a weird career - he had this pattern of following an outstanding season with two or three poor ones, often marred by injury. He was the 1979 Rookie of the Year when he won 17 games for the Dodgers. He won 3 and 2 games the next two seasons and was traded to Cleveland. He followed up his Cy Young year with the Cubs by winning 8 and 5 games before bouncing back with 18 wins in 1987. After winning 16 for the 1989 Cubs, he posted seasons with 0 and 6 wins. The Cubs let him walk - the Orioles signed him and he won another 16 games.

41. A hulking RH with a large moustache, Dick Tidrow holds the weird distinction of being one of just four players who played for both the Yankees and Mets, the White Sox and Cubs. He broke in with the Indians with a fine rookie year as a starter (14-15, 2.77) - the two seasons that followed weren't nearly as impressive. He was traded to the Yankees and after another mediocre year in the rotation, he Found His Destiny. It was setting up the closer, Sparky Lyle. Alas, injuries forced him back into the rotation in 1978. This didn't work out, so the Yankees got rid of him. Traded to the Cubs, he resumed his old set-up role, this time in front of Bruce Sutter.

42. The Hall of Fame plaque notwithstanding, Bruce Sutter was not as good a pitcher as Tom Henke. (I will die on this hill, I promise!) As good as he was (and at his peak, he was really, really good), Sutter simply wasn't as effective as Henke and he didn't last as long (partially because he was worked much harder. Both were late inning specialists who never made a single start in their careers, but while Sutter appeared in just 19 more games than Henke he pitched an extra 252 IP.) But Sutter's historical significance is undeniable. Baseball managers had spent almost 30 years unable to discover the optimal usage of their late inning relief aces. In 1978 and 1979, Sutter was simply untouchable in the first half of the season, and much more hittable in the second half. This persuaded his manager to simply impose limits on his closer's workload, to prevent him from running out of gas as the season went on. It worked like a charm, and the rest of the game soon followed suit. It means that Sutter is an important turning point in the usage of relief pitchers. He was also one of the first pitchers to make his living with the split-finger fastball. This wasn't the old forkball, which was more of an off-speed pitch. Sutter's pitch acted rather like a spitball (and some of the splitter artists who followed in his wake were definitely doing something to the baseball. I'm looking at you, Mike Scott.)

43. This is the spot I found for Bill Nicholson! He took over in RF in 1939 and played quite well for three years. Then, two things happened: Nicholson switched from number 8 to 43, and a whole lot of Americans went off to war. Some of them were baseball players. NIcholson promptly led the NL in HRs and RBIs in both 1943 and 1944. Then his game fell apart. He was later diagnosed with diabetes, which may have been a factor.

44. I expect a day will come when we'll have to give this one to Anthony Rizzo, although he'll need to play just a little more like the way he did in his 20s. It does seem unlikely that he's fallen right off the cliff. In the meantime, let's remember another left-handed Cubs firstbaseman. Phil Cavaretta. He had just turned 18 when he made his ML debut with the 1934 Cubs; the next year he was the every day first baseman for the NL pennant winners. He was a line drive hitter with excellent plate discipline but not too much power. Despite (or perhaps because of) the very early start, it took him a few years to get untracked - he broke his ankle in 1939 and again in 1940. He was exempt from military service because of a perforated eardrum and had his best seasons while many of the real players were away - he was the 1945 MVP when he hit .355 to lead the league. He wasn't really a star. But he was a solid regular, who appeared in 20 seasons for the Cubs

45. Sean Marshall was a big LH starter who moved into the Cubs bullpen after a couple of seasons in the rotation. He had his moments. Paul Assenmacher was a little better. He appeared in 884 games in the major leagues, just once as a starter - with the Cubs, of course.

46. I'm dubious about Lee Smith's Hall of Fame case - a late inning relief ace with a 3.03 career ERA? He spent about a decade as the all time saves leader, but by the time the Veterans Committee called his name he'd long been overtaken at the top of the list, first by Trevor Hoffman and then by Mariano Rivera. He was a decent closer, and he was certainly a frightening figure on the mound - he was really big, he looked really mean, he threw really hard. His long odyssey through the majors began with eight seasons in Chicago.

47. It's Dennis Lamp, again. He began his long career in the Cubs rotation and was actually pretty good, especially for someone never struck out anyone. Seriously - he pitched more than 200 IP three times and never fanned more than 86.

48. His nickname was Big Daddy, and Rick Reuschel's career was something of an adventure. He was the Cubs' ace starter through most of the 1970s, generally a dependable workhorse who'd give you some 250 IP a year. He did post 20 and 18 win seasons along the way. The Cubs traded him to the Yankees, and less than a year later he was having rotator cuff surgery. At the time, this was regarded as the great career killer. But Reuschel fought his way back, re-establishing himself as a quality starter with the Pirates and then finishing up with a couple of fine years with the Giants.

49. Bill Hands was a fine starter for those Cubs teams that just couldn't get over the hump in the late 1960s. Hands went 20-14, 2.49 for the 1969 team that was overtaken by the Miracle Mets. Jake Arrieta was a little better, with his Cy Young year in 2016 and his outstanding performance in the 2016 World Series. After three disappointing years in Philadelphia, he's back with the Cubs and seems to be picking up right where he left off.

50. Well, I guess Will Ohman had the one pretty decent year.

51. You know, Terry Adams wasn't that bad as a Blue Jay although I still have some awful, awful memories. He had his longest term with the Cubs, for whom he had his best season.

52. The most distinguished man here is Justin Grimm, who spent four years in the Cubs pen, collected a World Series ring, and is still around, looking for work somewhere I suppose.

53. Rich Hill began his lengthy, nomadic career in Chicago, and the only time Hill has made 30 starts and qualified for the ERA title was with the 2007 Cubs. Johnny Schmitz was another southpaw who pitched a long time, although the war took three seasons away from him. He was a very good pitcher for those awful post-war Cubs teams, going 18-13 in 1948 for a Cubs team that went 64-90.

54. Slim pickings indeed. Neil Ramirez had an outstanding rookie year with the 2015 Cubs, which earned him four more years of chances. And this is where Shawn Camp went when he left the Blue Jays as a free agent. Camp had one solid year with the Cubs. I always liked watching him pitch as a Jay, there was so little drama it was comforting.

55. Sometimes all you can do is settle for a backup catcher. You know, someone like Koyie Hill.

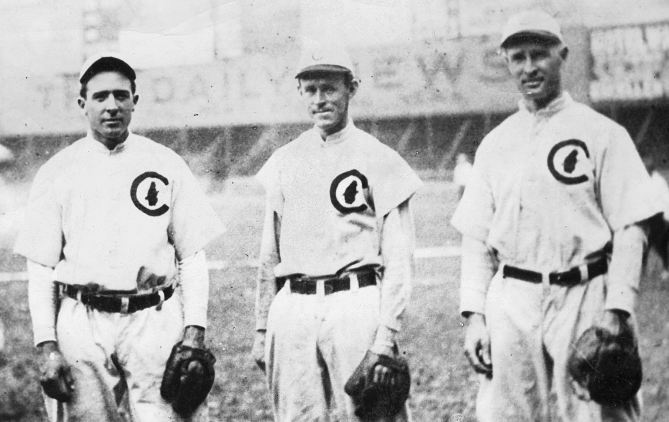

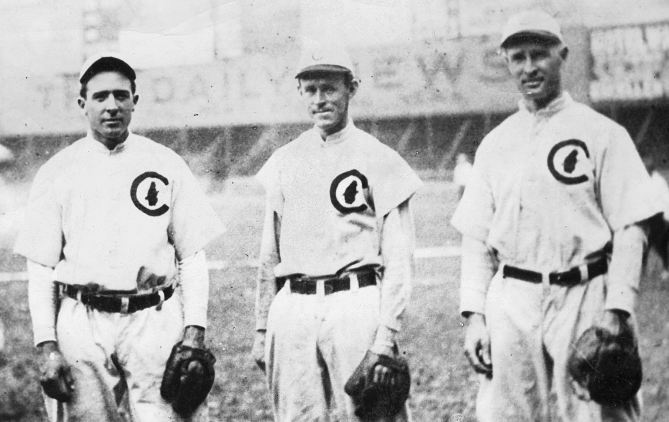

The Cubs have been pretty stingy with the high numbers. The only player of any note would be Jose Quintana (62). But their history is full of famous players who never wore a number on their backs. From the 19th century alone, we find Cap Anson, Bill Hutchison, John Clarkson, Larry Corcoran, and Bill Dahlen. The great teams from the beginning of the 20th century had outstanding pitchers: the Hall of Famer Mordecai Brown, of course, but Orval Overall and Ed Reulbach as well. There was the great catcher, Johnny Kling. And the infield trio immortalized as "Baseball's Saddest Lexicon:" the slick shortstop Joe Tinker, highly strung second baseman Johnny Evers (rhymes with "beavers"), and their tall Peerless Leader, manager-first baseman Frank Chance

These are the saddest of possible words:

"Tinker to Evers to Chance."

Trio of bear cubs, and fleeter than birds,

Tinker and Evers and Chance.

Ruthlessly pricking our gonfalon bubble,

Making a Giant hit into a double –

Words that are heavy with nothing but trouble:

"Tinker to Evers to Chance."

The 1920s teams never won anything but Pete Alexander and Hippo Vaughn certainly deserve to remembered. And we simply must not forget Hack Wilson. Lewis Wilson had a classic baseball body - he stood 5'6 and weighed as much as 230 pounds. He had a massive torso, short stubby legs, small hands and tiny (size 5!) feet. Both his parents were alcoholics and Wilson was probably born with fetal alcohol syndrome. He was an alcoholic by the time he arrived in Al Capone's Chicago in 1926. Joe McCarthy loved him and, it must be said, enabled him - constantly bailing Wilson out of jail when he'd been picked up in a raid on one of Capone's speakeasies. (McCarthy was not so forgiving of his other drinking men, who included the great Pete Alexander.) Wilson was a Cub for six seasons, during which time he led the NL in HRs four times. He was the first man (non-Ruth division) to hit 50 HRs in a season. He also set the single season record for RBIs with 191 - a record that has now stood, without serious challenge, for 91 years.

10 comments

https://www.battersbox.ca/article.php?story=20210429151112607