Lobby of Numbers: Detroit Tigers

Thursday, August 19 2021 @ 09:00 AM EDT

Contributed by: Magpie

When I was a little wee nipper, about eleven years old, I went exploring in an old trunk I found in the garage. And I found three battered old books. I rescued them, and read them, over and over.

One book was Seven Plays and Prefaces by George Bernard Shaw, which has profoundly shaped the way I think about and see the world from that day to this. (Those socialists, they're like the Jesuits. They get you when you're young and it's all over.) The other two were about baseball: one was without a cover or title page, but I eventually discovered that it was Arthur Daley's 1950 volume Inside Baseball, a collection of stories and anecdotes from the early days of the game. It seems pretty obvious to me now that this was where I first acquired my taste for Windy Baseball Lore.

The other was a history of the Detroit Tigers. Fred Lieb wrote a number of team histories shortly after the war, and my dad was a Tigers fan when he was a boy. So I'm rather well informed when it comes to the first half century of Tigers' history. (I haven't seen the book in at least forty years but I even remember one of the chapter titles: Five Dreary Years Under Bucky.)

The Detroit Tigers were one of the charter members in 1894 of the reorganized Western League, which rebranded itself as the American League in 1900 and as a competing major league the following year. Detroit is one of five Western League franchises who still comprise part of today's American League - they are the only one that retains the original team name. In fact, they are the only one still in their original city. The Sioux City Cornhuskers moved to Chicago in 1900. The Milwaukee Brewers moved to St.Louis in 1902 and finally to Baltimore in 1954. The Grand Rapids Rustlers moved to Cleveland in 1900, where they have just renamed themselves as the Guardians. And the Kansas City Blues became the first Washington DC franchise in 1901, although they've been in Minnesota since 1961. Only the Tigers have kept faith with their origins, along with - yes, the Mariners and the Blue Jays.

In just their fifth season in the AL, the Tigers were blessed with one of those enormous strokes of good fortune that changes the destiny of a team for decades. They added an 18 year old outfielder named Ty Cobb to their roster. Two years after that, they made the old Orioles shortstop Hugh Jennings their manager and immediately won three straight AL pennants. But they lost in the World Series each time and Cobb would spend the rest of his career weighed down by a supporting cast of has-beens and never-could-have-beens. Only twice were they even in contention - they spent the last month of 1915 nipping at Boston's heels but never could catch them. And in late September 1916, they went into Fenway tied for first with the Red Sox - and dropped three games in a row. Hugh Jennings moved on after 1920, and Cobb replaced him as a player-manager. Cobb was actually a pretty good manager, but he had nothing to work with. He was followed by his old teammate George Moriarty, and then the five dreary years under Bucky. But by 1934, Connie Mack was selling his stars for money - again - and the Tigers paid $100,000 for the great catcher Mickey Cochrane. The Tigers made him their manager (in the 1930s, half the managers in the game were active players) and Cochrane led them to the World Series in 1934, winning the MVP along the way. And in 1935, they were back in the classic and this time they finally won their first championship. And by this time, they had numbers on their backs, having begun doing so in 1931.

The Tigers have generally avoided using the higher numbers as much as possible, and by higher numbers we really mean anything above 30. Until fairly recently, if you were a decent player, you got a lower number. So I expect that it will be slim pickings indeed as we reach the end of this journey. But we get to start with someone of recent vintage, who was really, really good.

1. Where does Lou Whitaker stand on the list of all-time great second basemen? Pretty damn high, I can guarantee that. As far as I can tell, just five men accumulated more WAR playing second - Hornsby, Collins, Lajoie, Morgan, and Gehringer. That doesn't make Whitaker the sixth best second baseman of all time, but it certainly puts him in the discussion. His best years, good as they were, don't match the best years of Jackie Robinson, Rod Carew, or Roberto Alomar - but Robinson only played the position for five seasons, Carew for eight. Whitaker played second for eighteen seasons and never played even an inning at another position. Alomar's last good year came at age 33; Whitaker just kept playing, and playing well. When he was 21 years old, he was the Rookie of the Year - when he was 38, he hit .293/.372/.518 and that was when he decided to hang them up. It is simply bizarre that he doesn't have a plaque in Cooperstown.

2. Perhaps Whitaker's problem is that as good as he was, he wasn't the even the best second baseman in Tigers history. He had been preceded by another LH batting second sacker, a local boy who attended the University of Michigan, and then spent his entire major league career in Detroit. No one ever thinks of Charlie Gehringer as the greatest second baseman of all time, and I suppose that's reasonable. I myself always think the argument is between Collins, Robinson, and Morgan, and I usually conclude that Morgan surpasses Robinson for peak greatness and Collins surpasses Morgan for career greatness. Gehringer was actually a very similar player to Morgan, another great LH batter with some pop, a base stealer, a man who played outstanding defense. Morgan hit a few more HRs, drew lots more walks, stole many more bases - Gehringer hit for a much better average, drew lots of walks himself, and hit so many doubles and triples that he basically matched Morgan's power. Gehringer doesn't have Morgan's mighty five year peak - few players can match Morgan's five year run from 1972-76 - but the rest of Gehringer's career is simply better. Better than Joe Morgan. That's some kind of player.

3. The Tigers actually came up with a third LH second baseman in the years between Gehringer and Whitaker. This was Dick McAuliffe who first spent four seasons at shortstop before moving over to secondbase. McAuliffe was a good player at both positions, a very fine hitter who provided both power and plate discipline during the second Dead Ball Era. He also had one of the stranger batting stances in the history of the game. But McAuliffe obviously has to take back seat to Alan Trammell. I would expect you're all familiar with him. I think he's been slightly overrated, that he wasn't quite as good as his longtime DP partner Whitaker. At his peak, Trammell was rather similar to Derek Jeter as a hitter, except that what Trammell did for six years Jeter did for fifteen (Trammell was certainly a superior defender.) But still, he's very much a deserving Hall of Famer, who probably should have been the 1987 MVP (although Wade Boggs had a helluva case.) And while we're here we simply have to mention the great Mickey Cochrane, who wore this number when he came over from Philadelphia in 1934.

4. Goose Goslin was a key contributor to those Tigers' pennant winners in the 1930s, but Goslin put himself in the Hall of Fame with his work ten years earlier in Washington. By the time he got to Detroit, he was an aging RBI guy (a mighty good one, though.) So we're remembering Rudy York here. He was universally thought of as an "Indian" while he was active - he was one-quarter Cherokee - and he was always a man who could hit but was a bad defender no matter where he played. He started out playing in semi-pro leagues in Georgia. The Tigers signed him to their Class C team in 1933 and an injury to the regular put him behind the plate. By 1937 he was in the majors, proving that a) he was one of the most dangerous RH batters in the league and b) he was never going to be a major league catcher. Finally, in 1940, the Tigers persuaded their superstar first baseman Hank Greenberg to move to left field, clearing first base for York. Installed at the one position in the field he could handle, York helped the Tigers win a pennant in 1940 and a championship in 1945. At some point, however, Detroit fans turned on him - with Greenberg away at war, York was easily the team's most dangerous hitter. It's always the best player who gets the heat when a team disappoints its fans. After the 1945 championship, with Greenberg back from the war and needing to return to first base, York was traded to Boston. He only had one decent season left and was finished at age 35.

5. Jim Northrup was a very fine player, one of the heroes of the 1968 World Series win, and a Michigan boy to boot. But Hank Greenberg was the second or third greatest player in franchise history. He did this while coping with the same sort of abuse Jackie Robinson would have to endure a decade later. Greenberg was the son of Jewish immigrants from Romania and while he once said that he had never particularly strongly identified as a Jew, the fans and the opposing players reminded him at every possible instant. Hitler and his ideas had a genuine following in the America of the 1930s. It was very, very ugly. Like Robinson, all he could do was play, and play so well no one could say anything about it. He was the MVP in 1935 when he hit .328/.411/.628, drove in 168 runs and led the Tigers to their first championship. He lost almost the entire following season to a wrist injury but bounced back in 1937 with 40 HRs and 183 RBI. The next year, he made a run at Babe Ruth's HR record, falling just short with 58. And in 1940 he had possibly the finest year of all. He moved from first base to left field to accommodate Rudy York, while hitting .340/.433/.670 with 41 HR, 150 RBI, winning his second MVP and leading Detroit to another pennant. He was 29 years old. And then he was drafted. After missing most of the 1941 season in the Army, Pearl Harbour happened and Greenberg re-enlisted. He was 34 before he played another major league game, but he returned in time to help the Tigers to their second championship. He arrived as a full-time player when he was 22 and retired at 36, but he was only able to play more than 100 games seven times. And yet, as great as he was - and that was very great indeed - there were two other players active in the same league at the same time, playing the same position who were even greater. Which boggles the mind, but from 1933 through 1938, when all three were active, either Jimmie Foxx (1933, 1938) or Lou Gehrig (every other year) was even better than Greenberg. Which I suppose makes him the Roberto Clemente (Aaron and Robinson) or Duke Snider (Mantle and Mays) of his time.

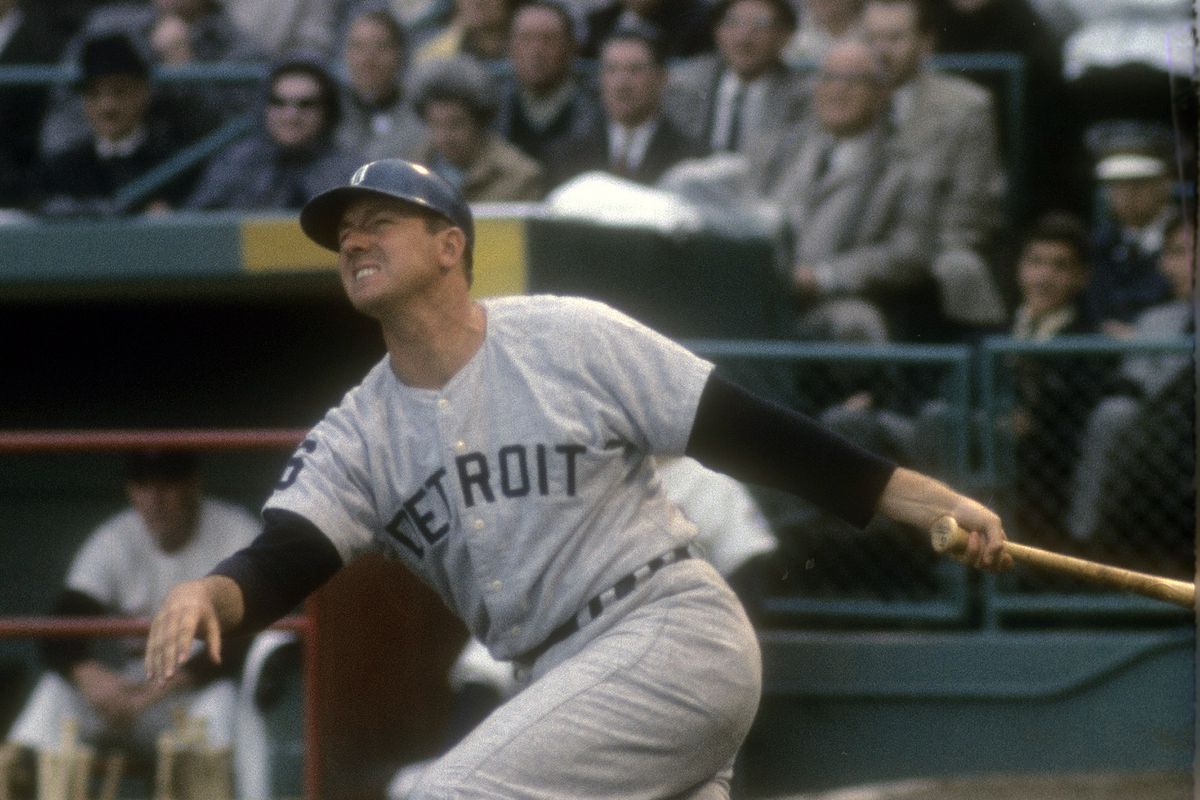

6. The reason Greenberg may only be the third greatest Tiger of all is because Al Kaline was just about as good, albeit in a different way and at a different time - and Kaline played literally twice as many games in the majors. The Tigers signed him out of a Baltimore high school in 1953, when he was 18. As a bonus baby he was required to spend two years with the major league team before he could be sent to the minors, and this was Detroit's plan for Kaline as well. But he was third in the Rookie of the Year voting in 1954 while still a teenager, and in 1955 he became the youngest man ever to lead the AL in hitting. He never would play a single game in the minors. In some ways Kaline was a little like Henry Aaron, playing the same position in the other league. Their careers as Braves and Tigers overlap almost perfectly. Obviously Kaline wasn't as good as Aaron, one of the greatest baseball players who ever walked the earth. But you don't have to be as good as Henry Aaron to be a great player yourself. While Aaron was an all-time great, Kaline was merely a very good hitter, for both power and average. While Kaline hit home runs - 399 in his career - his season high was just 29. Kaline ran very well but not as well as Aaron, and Kaline definitely didn't have Aaron's remarkable durability. But he was an even better outfielder, and just like Aaron he kept stamping out one excellent season after another for almost two decades.

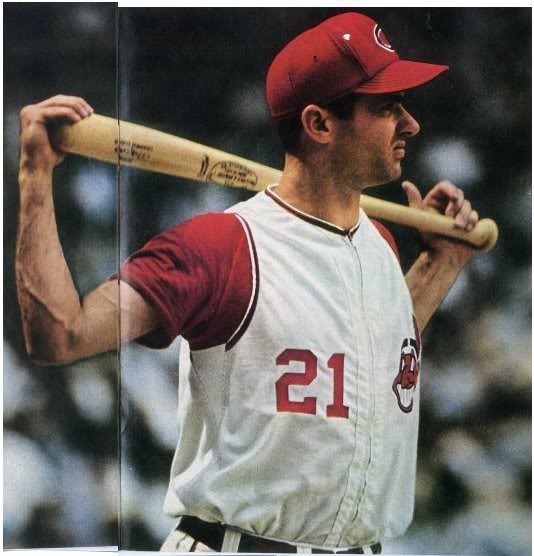

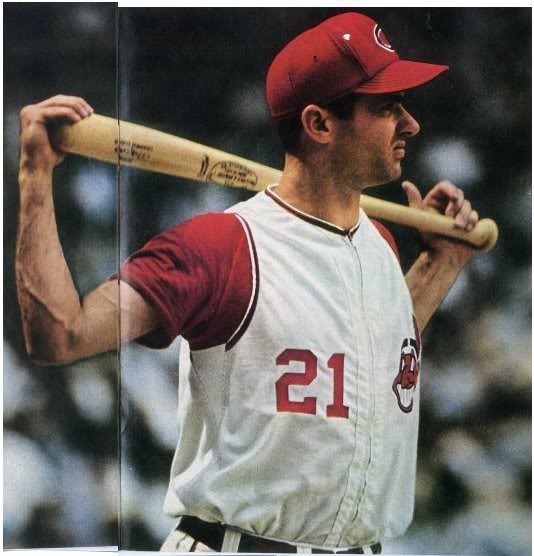

7. In the early 1950s, the Tigers came up with a young shortstop named Harvey Kuenn. He wasn't the greatest shortstop and he had no power, but he could hit line drives pretty much at will. In his first season, he led the league in hits with 209 and was the Rookie of the Year. He hit .314 in his seven years as a Tiger, led the league in hits four times, and won the 1959 batting title when he hit .353. Kuenn had gotten a little too big for shortstop and been moved to the outfield by this time. Which was when they traded him to Cleveland in one of the most notorious trades ever made. Coming back to Detroit was Rocky Colavito, who had just led the AL in home runs. He was also three years younger than Kuenn, but Cleveland GM Frank Lane was pretty proud of his cleverness. He quipped that he'd just exchanged hamburger for steak. And indeed there was a genuine debate in the moment as to whether Colavito's home runs were more valuable than Kuenn's singles. Honest, there was. Kuenn lasted just one year in Cleveland. Colavito spent four seasons in Detroit, hitting .271/.364/.501 with 139 HRs and 430 RBIs. He had something of a down season in 1963 (it was still pretty good), the first year of the Expanded Strike Zone, and the Tigers traded him to Kansas City. He spent his final five seasons wandering from team to team, finishing up with the Yankees in 1968. Colavito also had one of the best throwing arms in the league - while he played LF in Detroit (Al Kaline, even better) he spent most of his career in RF. I was a little boy when Colavito played, but he had a mannerism before he stepped into the batter's box that I've never forgotten because I copied it as a kid. He lifted the bat over his head and held it behind his shoulders as he stretched out his upper body muscles (the best picture I could find shows him in a Cleveland jersey, alas.) The things we remember.

8. The original Boone was third baseman Ray, father of Bob and grandfather of Bret and Aaron. He was a bit of a late bloomer and gave the Tigers by far the best years of his career. He was certainly a better player than Don Wert, who held down the same job for seven seasons in the 1960s. Ron LeFlore was a better player and a better story. He came from the hard streets of east Detroit, and after a childhood of truancy, petty theft and reform school he made it to the major leagues - Jackson State Prison, where he began serving five-to-thirteen for armed robbery in April 1970, when he was 21 years old. Which is where he started playing baseball. Where a friend (a fellow inmate) of a friend happened to know Billy Martin, who came to the prison in May 1973 and arranged a tryout during a weekend furlough a few weeks later. LeFlore was released from prison the following month and made his pro debut in A ball, where his first manager was Jim Leyland. One year later he was in the Tigers outfield. He was an odd player - he had remarkable natural ability, but he didn't really know how to play baseball. And he didn't really know how to live in the world. Why would he? He had, after all, spent his youth engaged in other pursuits and the Tigers were certainly not the best organization to give him the help and guidance he badly needed. And major league stardom probably wasn't the best thing that could have happened to him. The fact that he made it as far as he did was improbable enough.

9. In one of the worst challenge trades ever, Seattle and the Tigers swapped shortstops in January 2004. The Mariners got Ramon Santiago who failed to make the major league team, hit .193 in the PCL, and was released a year later. The Tigers got Carlos Guillen, who didn't have the greatest glove, but could really hit - .313/.377/.506 over the next four seasons - before a variety of leg injuries gradually ground his career to an end.

10. Rusty Staub spent three productive seasons in Detroit, as he evolved gradually from an outfielder to a DH to a pinch hitter deluxe. But Tommy Bridges is more important to the Tigers' story. Bridges was one of just 13 men to lose a perfect game with two outs in the ninth inning (actual perfect games have happened more often) - in his case, it was a pinch-hit single that broke it up. He was a slightly built curveball artist from Tennessee who capped the Tigers first World Series win by retiring Jurges, French, and Galan as the go-ahead run stood on third base. The Tigers scored the walkoff winner in the bottom of the inning. That was Bridges' second win in as many Series starts, the second of his three straight 20 win seasons, the first of his two seasons leading the AL in strikeouts. At some point during the war, Bridges developed a taste for liquor that soon turned into utter dependency. His marriage fell apart. His old teammate Billy Rogell found him lying in the street and tried to help him out, with little success. Towards the end of his life, he seems to have finally overcome his problems enough to find work as a scout, for the Tigers and then the Mets.

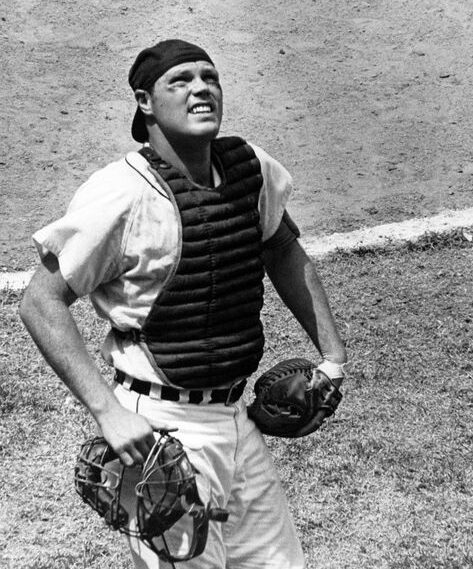

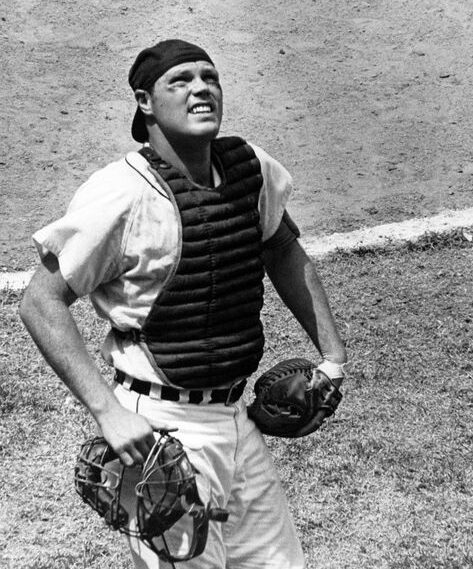

11. For about a decade, Bill Freehan - a Detroit boy who went to the University of Michigan - was the best catcher in the American League. It's something everyone knew at the time - he made it to 11 All-Star games and started behind the plate in seven in a row. He was the MVP runner-up in 1968, having finished third in the voting the year before. He's been overshadowed a little by the AL catchers who came after him - the Fisk-Munson-Sundberg generation - and his offensive numbers, which are just fine anyway, were certainly depressed somewhat by the Expanded Strike Zone. His career ended a little early. The Tigers seemed downright impatient to move on from him, for reasons that surpasseth all understanding. They traded for Milt May and when May got hurt, they tried to force Bruce Kimm and John Wockenfuss into the position. They gave his Freehan his release after he'd hit .270/.303/.384 at age 34 in 1976. Freehan decided he'd already been lucky to spend his entire career playing for his hometown team and chose to retire.

12. The long and winding road that Bobo Newsom trod in his lengthy career began in 1929 when he faced High Pockets Kelly and the Reds as a Brooklyn Dodger - it finally ended in 1953 with a bullpen appearance for the A's when he pitched to Cleveland's Al Rosen and Larry Doby. He spent most of his career working for awful teams - he pitched in eight seasons for the Senators, five for the Browns, another five with the A's. In 1938 he won 20 games for a Browns team that went 55-97 and the following season he found himself in Detroit, on a good ball club. He went 41-16 over the next two seasons and was the outstanding performer of the 1940 World Series. But after one more year in Detroit, his wanderings resumed.

13. The Tigers eventually found an adequate replacement for Freehan, once Milt May and Bruce Kimm had been found wanting. Lance Parrish was a slugger who played good defense (three Gold Gloves) had a rifle arm, and managed his pitchers. He was a big guy for a catcher, which may be one reason he had back issues almost his entire career, and he didn't do a whole lot else with the bat besides hit home runs. But he hit more than 300 of them and made eight All-Star teams. The Tigers let him walk after his age 30 season, and he wandered the majors for the back half of his career.

14. Jim Bunning was a tall RH from Kentucky - he's in the Hall of Fame and when he was done with baseball he served in the US Congress for twenty-four years, the final twelve as the Senator from Kentucky. He was very good with the Tigers, but even better (and much more memorable) for the Phillies. So we'll single out Schoolboy Rowe instead. He was a tall RH from Texas, who went 24-8 for the 1934 team and ran off 16 consecutive wins to tie the AL record (it's since been broken.) After three fine seasons in Detroit his shoulder went bad. He made just 5 starts, winning only once in 1937 and 1938. One day, he tried stretching out his right arm as far and as hard as he could and heard a sound like a pistol shot. And the pain in his shoulder suddenly and completely disappeared (Catfish Hunter would have the exact same experience in 1978, but he'd been put under anaesthetic for the procedure.) And that's how Rowe was able to go 16-3 for the 1940 pennant winners.

15. Joe Coleman was the third player taken in the inaugural major league draft in 1965. Just 18 years old, he instantly made his MLB debut and pitched a CG four hitter to win it. The Senators were a terrible team, but Coleman was lucky enough to go to the Tigers in one of the game's more lopsided trades (the Senators also sent Detroit the left half of their infield in exchange for Denny McLain and Don Wert, both of whom had large forks sticking out of their backs.) Coleman won 62 games in his first three seasons in Detroit. Alas, his arm basically fell off at age 28 after four straight seasons of more than 280 IP. He was a good one. But Don Mossi was a legend. A fine pitcher, sure, a hard-throwing LH with outstanding control. But that's not what made him famous. It was that face, a face that only a mother could love. And she might have been jiving, too.

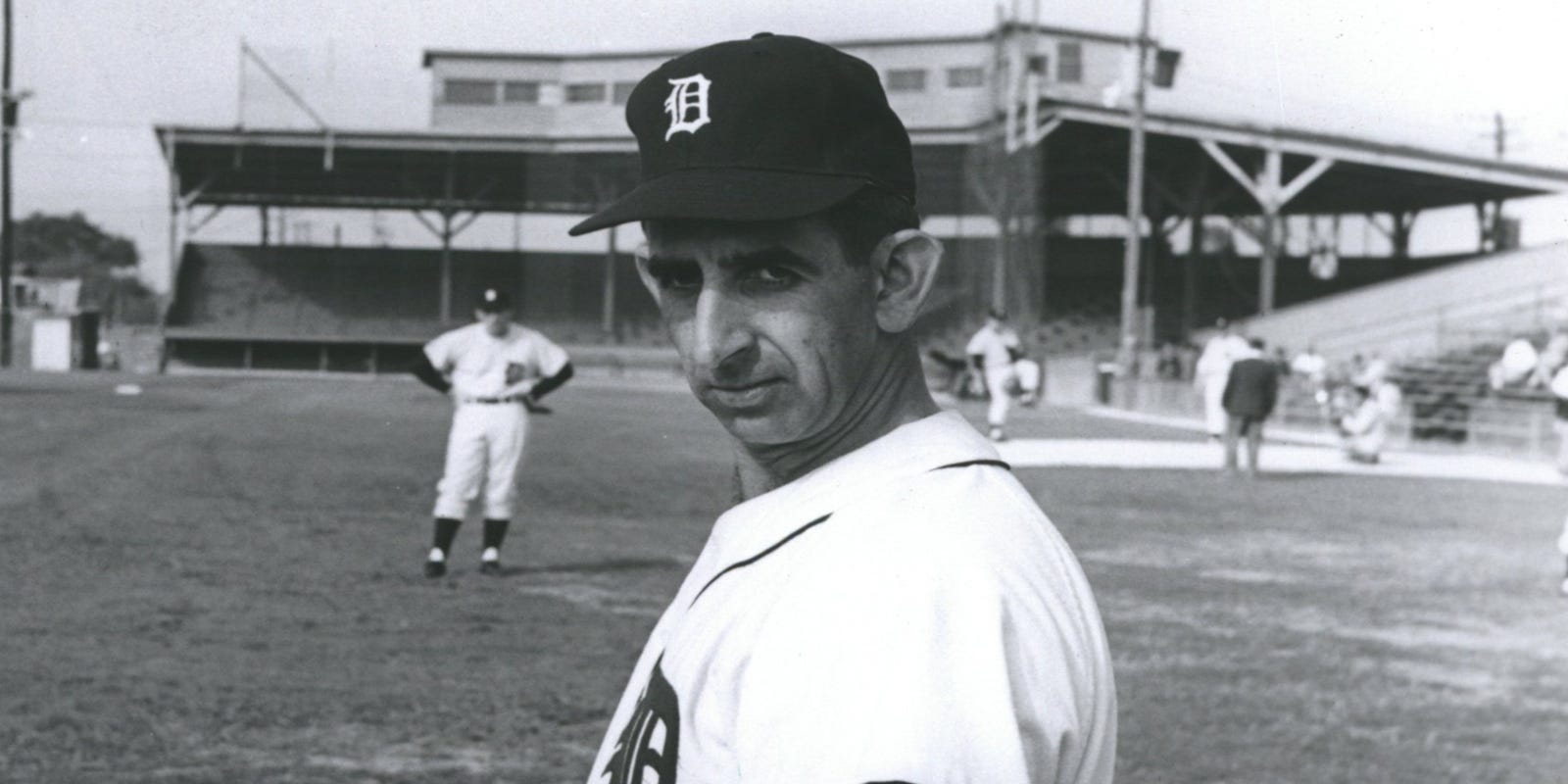

16. Stop me if you've heard this one before - hard throwing LH unable to throw strikes suddenly finds the strike zone and simply explodes on the league. Hal Newhouser was another Detroit boy and he was still a teenager when he joined his hometown team. He struck out as many batters as anyone in the league, he was impossible to hit, but he walked just as many as he struck out. After four seasons, he was 34-52, 3.69 with 446 Ks and 442 BB in 690 IP. And then, in 1944, he found the strike zone. Over the next three seasons, he went 80-27, 1.99, leading the league in wins all three seasons, in Ks twice, ERA twice - and becoming the only pitcher to win consecutive MVP awards. Yes, there was a war on with this started. The war was over by 1946 and Newhouser was still dominating the league. He fell off from those heights but remained a very fine pitcher for three more seasons until shoulder miseries ground him down. He was famous for his fiery temperament when he was a player and it was speculated that it was when he learned to control his temper that he learned to control his pitches. Newhouser said it was the other way around - once he started winning, he had no reason to get angry. "I'll always be a hothead, it's just the way I am." He spent many years scouting the Michigan area for a variety of major league teams - he found Milt Pappas for the Orioles - and he quit his final job, with Houston, in a huff when they drafted Phil Nevin instead of the kid Newhouser had been pushing for, a shortstop from Kalamazoo High named Jeter.

17. Denny McLain wasn't a one-year wonder - he did win two Cy Young awards - but he only had three good seasons. Frank Lary had twice as many, and was one of the very few pitchers famous for his ability to beat one opponent. That opponent was the best team in the league - Lary went 28-13, 3.32 against the Yankees. He went 100-103, 3.52 against the rest of the league. Which was why he was known as the Yankee Killer.

18. Of course he would have rather been a hockey player, but John Hiller did just fine playing ball. He spent his entire career working mostly out of the Tigers bullpen, won a World Series ring in 1968, and after missing more than a year recovering from a heart attack, fought his way back to have one of the finest seasons any relief pitcher had ever had - 10-5, 1.44, a record 38 saves.

19. Here's a strange claim to fame - Al Benton was the only man who pitched to both Babe Ruth (in 1934) and Mickey Mantle (in 1952). Bobo Newsom just missed - he pitched to Ruth, but Mantle was out with an injury when he faced the Yankees at the end of his career. Benton was a big RH from Oklahoma who spent nine seasons with the Tigers, moving between the bullpen and the rotation, but pitching effectively whatever role he was in.

20. Vic Wertz was a fine player, a dangerous LH batter who played for seventeen seasons but he's mostly remembered for a ball he hit in the 1954 World Series that was caught by the centre fielder. Doesn't seem fair. We're passing him by here as well. There was only one Mark Fidrych. He just had the one season, and he probably wasn't bound for glory even if he hadn't been worked far too hard as much too young an age - but that one year was pretty special. It's my belief that Fidrych in 1976 is the only player in the last fifty years who actually had a significant, measurable impact on game attendance. He certainly had a far greater impact than Fernandomania (which is the other one everyone mentions.)

21. The Hall of Fame has made some puzzling calls over the years, and to my mind honouring George Kell was one of them. He was certainly a good player, and he led the AL with a .343 average in 1949. It's possible that the AL simply had a shortage of good third basemen while he was around, which is why he made it to ten All-Star games. The flashy BAVGs certainly helped.

22. In September 1945, Virgil Trucks rejoined the Tigers for the season's final weekend after two years in the navy. He'd gone 16-10, 2.84 for the 1943 team, but he hadn't pitched in the majors since. He started one of the two crucial weekend games - his bullpen blew the lead, but the Tigers rallied to win anyway. He then pitched a CG victory in the second game of the World Series. Not a whole lot of rust on Virgil Trucks.

23. I think we snub Kirk Gibson, yet another Michigan boy, at our own risk. I'll take the chance. Gibson was good, but Willie Horton was just a little better for just a little longer. Both were sluggers who didn't hit quite as many HRs as you expect from "sluggers" - the only 30 HR season from either was the 36 Horton hit in 1968. Neither man was a great outfielder. Gibson was much faster, Horton threw much better (and indeed, had a key BaseRunner Kill in the 1968 World Series, nailing Lou Brock at home.) Horton was a slightly better hitter during their Detroit years, and quite a bit more durable. It's pretty close.

24. These days, he's barely a fragment of the mighty offensive force he was ten years ago. And Miguel Cabrera is under contract for two more seasons at $32 million per. Ouch. But he had a twelve year run as one of the greatest RH batters the game has ever seen - .326/.405/.571, averaging 36 HR and 122 RBI, an OPS+ of 159. For twelve seasons. He collected two MVPs along the way, and put together the only Triple Crown season in the last fifty years.

25. One of the most famous fluke seasons in the game's history was the one turned in by Norm Cash in 1961, when he hit .361/.487/.662 with 41 HR and 132 RBI. All these figures were career highs, by a considerable margin. Cash was a good player his entire career, but he never hit higher than .283 in any of his other 16 seasons. He did have four other seasons when he cleared 30 HRs, and he always drew plenty of walks. He once went up to the plate against Nolan Ryan, one out away from a no-hitter, with a table leg rather than a bat saying he had as good a chance with it as anything else. On another occasion, he was standing on second base when a rain delay came. When play resumed, he tried to go to third base. He told the umpire he'd stolen it, and when asked when, replied "while it was raining." He was an awful a lot of fun, and he had a lot of fun. It contributed to his early death - he slipped off a dock, hit his head, and drowned. He'd had too much to drink. He was only 51.

26. The Angels in the early 1970s had the two hardest throwing pitchers in the AL - Nolan Ryan, who was pretty good, and Frank Tanana who was quite a bit better than Ryan. But Tanana hurt his arm, lost his fastball forever, and spent five full seasons scuffling. But he learned how to get by with a mid 80s fastball and his curveball. He made it to Detroit, his home town, when he was 31 and lasted another eight seasons in the rotation. In the final week of the 1987 season, he made two starts against the Blue Jays. He allowed no runs in either of them, and his season ending shutout punched Detroit's ticket to the post-season.

27. I suppose we're stuck with the game's more notable LOOGYs. Mike Myers led the AL in appearances in both of his Detroit seasons.

28. Detroit was where J.D. Martinez found his stroke after being released by Houston - the Tigers traded him before free agency for Sergio Alcantara and Dawel Lugo. Oh well. Curtis Granderson came up with the Tigers, and after four fine seasons in Detroit, he and Edwin Jackson were the price the Tigers paid to get Max Scherzer and Austin Jackson. That worked out much better.

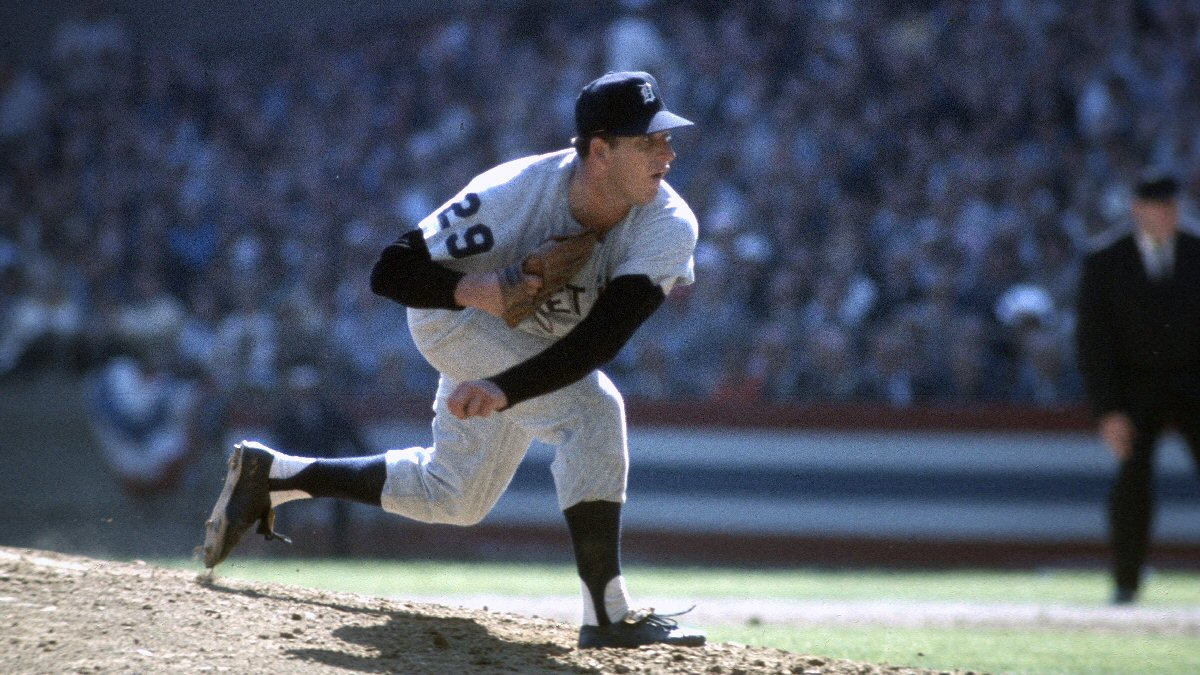

29. I would imagine that most people remember Mickey Lolich for his brilliant work in the 1968 World Series, when he tossed three CG victories, beating Bob Gibson himself in the finale. As they should. I also think of the utterly insane workload he carried when Billy Martin took over as the Tigers' manager in 1971. Lolich made 45 starts, pitched 376 innings, and went 25-14, 2.92 with 308 Ks. He spent most of his career as one half of a lefty-righty tandem at the top of the Tigers' rotation. The RH half changed over and over - from Dave WIckersham to Earl Wilson to Denny McLain to Joe Niekro to Joe Coleman, but Lolich was always there. He spent thirteen seasons in Detroit, and no LH won more games as a Tiger.

30. The Tigers signed Magglio Ordonez, a 31 year old outfielder who'd been with Chicago, to a big five year free agent contract in 2005 and for the first year it looked like a mistake. Ordonez missed half the season with a hernia while Jermaine Dye replaced him with the White Sox and was the MVP of Chicago's World Series win. But Ordonez spent the next four years more than making up for it, beginning with the very next season when he helped the Tigers reach the World Series. A series of leg injuries ground him down. He ended his career on an 18 game hitting streak, the longest ever by a player at the end of his career. (Ed Delahanty had hit in 16 straight games before he fell off that train in 1903.) Back home in Venezuela, Ordonez went into politics after baseball was over, and - unusually for a wealthy ball player - positioned himself on the leftist end of the spectrum.

31. The Tigers picked up Larry Herndon in exchange for a couple of pretty marginal LH pitchers. He'd spent six years with the Giants, playing mostly in CF, and hitting a few singles. In Detroit, he unexpectedly found a power stroke. After hitting 24 HRs in his entire career in the NL, he hit 23 HR in his season with the Tigers and 20 more the following year. He never approached those figures again, but he hit a couple more important dingers for Detroit in the 1984 post-season. And of course, in the 1987 season finale, he took Jimmy Key deep for the only run of the game, to give the Tigers the 1987 AL East title.

32. I can barely remember Jamie Walker, who was a pretty decent LOOGY for five years in Detroit.

33. The Tigers chose Steve Kemp out of USC with the first overall pick in 1976 and he took over left field a year later. He was an aggressive, hustling line drive hitter who played very well for five seasons - .284/.376/.450 - but with one year left before free agency, the Tigers traded him to the White Sox. After a year in Chicago, Kemp signed with the Yankees. In his first year in the Bronx he was hit in the face by a random line drive during BP. It caught him just below the eye, shattered his cheekbone, and inflicted lasting damage to his vision. A year later, he tore his rotator cuff. The game isn't always fair.

34. The player coming back from the White Sox in the Kemp trade was Chet Lemon, who had been a very fine centre fielder with the White Sox but who was - like Kemp - a year away from free agency. Lemon was a dangerous line drive hitter and a fine centre fielder - in 1977, he made 509 putouts in CF which is still the AL record and the third highest total of all time. He actually spent his first season in Detroit playing right field. First, Sparky played Kirk Gibson in centre for the first three months. (Apparently, the thinking behind this was that Gibson, who had been an outstanding football player in college and played baseball with the same aggression, wouldn't be as likely to run into a wall if he was playing in centre.) After Gibson went down for the season with a wrist injury, rookie Glenn Wilson - a man with one of the finest throwing arms of the decade - took over in... centre field. Go figure. But Sparky got it all properly figured out the following year and Lemon gave the Tigers nine good seasons.

35. The greatest pitcher in the long history of this franchise is Justin Verlander, who needs no introduction. Well, it's Verlander or Hal Newhouser, I suppose, but I say it's Verlander.

36. The Weaver brothers were both highly touted pitching prospects, both were drafted in the first round, both pitched in the majors for more than ten years. Jered Weaver would prove to be the better player of the two - Jeff Weaver was the older of the two brothers and Jeff wasted the best years of his career on utterly wretched Detroit teams.

37. The Tigers came away with Max Scherzer in what was a steal of a deal for them, and Mighty Max begin building his legend in Detroit. He went 82-35 in his five seasons as a Tiger, which is not too shabby, and won his first Cy Young Award in Detroit. He left as a free agent and got even better - much, much better in fact - after he turned 30. Well, it's hard to see that coming.

38. Poor Jeremy Bonderman. He was the player to be named later when Oakland was unloading Carlos Pena, and the Tigers stuck him into the rotation the very next season. He was 20 years old, on the very worst team of the last 50 years. It did not go well (6-19, 5.56). But he hung in there, he continued to develop, and just as he was becoming a quality starter and just as the team was getting good - the arm miseries began. At least he got to pitch in a World Series before it was over.

39. The relief ace - not the closer - of those late 1980s teams was Mike Henneman. Sparky Anderson, by this time, was very much an old school type of manager and he didn't use Henneman as a one inning guy to finish the game the way everyone else did and does. He used Henneman when it was late and the game was close and he used him for more than an inning if that's what was called for. That would probably work today, but it would require an awful lot more thinking than your modern manager likes to do.

40. Well, there's Nelson Cruz... oh wait. Wrong Nelson Cruz. We have to settle for Doug Bair, I guess.

41. Darrell Evans was a terrific player, but he was very much nearing the end of his career by the time he got to Detroit. Besides, we already called his name out as a Giant (that's not a rule, it's just an excuse.) Victor Martinez was a marvellous hitter, especially for a catcher. He wasn't really a catcher by the time he got to Detroit, and he lost a full season to a torn ACL. But he could still hit, and was the MVP runner-up for the 2014 Tigers when he was a 35 year old DH.

42. Apologies to Buddy Groom, who broke in with the Tigers, but if I get the chance to say it's Lima time... It's Lima Time! I'm aware that Jose Lima didn't pitch very well in Detroit. I don't care.

43. Generally pretty slim pickings in this neighbourhood, but Carlos Pena initially established himself as a decent major league hitter during his time in Detroit. Then he had a bad season at age 27 and they released him.

44. The first, and still the best, Tiger to wear this number was Billy Hoeft who was a decent enough LH starter for those early 1950s Detroit teams. He actually won 20 games in 1956. He had a lengthy post-Detroit career wandering the majors as an itinerant LH reliever.

45. One of the casualties of Toronto's Sil Campusano insanity was Cecil Fielder, who simply couldn't get into the lineup with Bell at DH and McGriff at 1b. Fielder didn't start a game as the DH until May 30. Playing irregularly, he had a poor season and the Blue Jays sold him to the Hanshin Tigers at the end of the year. After a season in Japan, he came back to North America to play for Detroit's Tigers. I think you all know what happened next.

46. Jack Morris' running mate in the early 1980s was Dan Petry, father of Jeff. Dan Petry was every bit as good at Morris - he just didn't last nearly as long. Petry only made it through four full seasons alongside Morris at the top of the rotation before his elbow stopped working the way elbows are supposed to work.

47. Very few players provided as endlessly controversial a Hall of Fame debate as Jack Morris. He was eventually inducted, so the argument is over. Despite his many years in Detroit, Morris is probably best remembered for his work for the Twins in the 1991 post-season (4-0, 2.43) and in particular his performance in the series finale. But his post-season work for the Tigers in 1984 (3-0, 1.80) was equally impressive. Morris was a little like Don Sutton - he was never the best, but he was certainly one of the best pitchers in his league for more than a decade. Morris often gets disrespected because of the quality of the teams he played for, as if being the top starter on a good team is some kind of disqualification. Not to mention, the man is something of a jerk. Blue Jays fans never did warm to him, and they never will. They generally prefer to belittle him and all his works, and saying anything vaguely complimentary about Morris always provokes them. So I'll point out that the Jays don't win anything in 1992 without him. Only Mickey Lolich started more games in a Detroit uniform.

48. You don't need to remember Rick Porcello - it's a little surprising that no one seems to have even given him a look this season, although I suppose most teams were somewhat put off by last year's 1-7, 5.64 mark. He was generally just a league average inning-eater, if that, but he's won 150 games in the major leagues and actually won a Cy Young award along the weay. Because baseball is just weird sometimes.

49. Jays fans will remember Jason Grilli, who pitched for nine different teams in his career. He was with the Tigers fairly on and had a couple of very fine years in their bullpen.

50. The Tigers drafted Andrew Miller sixth overall in 2006 and a little more than a year later he was part of the package that went to Florida in the Miguel Cabrera deal. He eventually went to the Red Sox who made a reliever out of him and he was pretty awesome for about eight years.

51. No one did anything of note, so we'll go with Gabe Kapler who had a decent enough rookie season with the 1999 Tigers and is a few months away from being named the National League's Manager of the Year.

52. Hey, it's Jose Bautista! Oops, wrong one. Hey, it's John Farrell! Who finished his playing career by making two starts for the 1996 Tigers and losing them both. Yes, 0-2, 14.21 - that should keep his memory alive in the Motor City. We're left with Chad Durbin, who was a decent enough swingman for the 2007 team.

53. Another well-travelled reliever, Joaquin Benoit had three fine years for Detroit in mid-career.

54. One injury after another was endured by Joel Zumaya, a RH reliever who threw very, very, very hard. He was unavailable for part of the 2006 post-season because of wrist inflammation suffered while playing "Guitar Hero." In 2007 he ruptured a tendon in a finger. That off-season he hurt his shoulder moving items out of his parents' California home as wildfires were encroaching. In 2009, there was a wrist injury and finally in mid 2010 he actually broke a bone in his elbow delivering a pitch. He tried to come back in 2012 and blew out his UCL in his first throwing session of spring training and, probably wisely, chose to retire.

55. John Cerutti finished his career here, but Mark Redman's year with the awful 2002 team was better.

I was struck while working on this by how many memorable Tigers actually come from the Detroit area - Gehringer, LeFlore, Northrup, Freehan, Gibson, Newhouser, Tanana. I didn't even mention Mickey Stanley and Dave Rozema. And they traded away John Smoltz. I didn't notice this when I was doing the Chicago teams. Maybe I just wasn't looking. Anyway, the Tigers have avoided using high numbers in general and strange ones in particular. We're only going to mention Todd Jones (59) because his 235 Saves remains the franchise record. We do have a few notables to call out from the days before they wore numbers at all. George Mullin, a durable innings-eater won 209 games as a Tiger and pitched very well in the three World Series defeats under Jennings. Wahoo Sam Crawford was that team's right fielder, a Hall of Fame outfielder who retired at age 37 with 2,961 hits. Obviously, no one was keeping track. Hooks Dauss was a curveball artist (naturally) who won more games than any other pitcher in team history. And Harry Heilman was one of the greatest RH batters of all time before arthritis in his hands helped end his career a little early. He had a long and successful run on the Tigers' radio broadcasts before lung cancer took him when he was just 56.

But after more than 125 years of Detroit Tigers baseball, one player stands far above all the rest.

Tyrus Raymond Cobb is one of the game's mythic figures, as a player and as a man. The legend looms much larger than the reality, and early biographers like Charles Alexander and, especially, the egregious Al Stump indulged in embellishments and fictions to such a degree that the well has probably been poisoned forever. There's the lazy assumption that anyone born in rural Georgia in 1886 must have been a vicious racist, but Cobb came from an abolitionist family. His grandfather had refused to fight in the Confederate army because of slavery, his father was a state senator who had advocated on behalf of his black constituents, and Cobb himself was a strong supporter of the integration of the game, saying black players "should be accepted wholeheartedly, and not grudgingly." It's true that he had some fights with black men, but he had many more fights with white men. You might say that Ty Cobb was an equal opportunity fighter. He may indeed have been a racist, but there were many who were worse than he.

He worshipped his father - "the only man who ever made me do his bidding" - but while his father wanted his son to take up a profession, the boy took no interest in his studies. The law or medicine were not for him - all he wanted to do was play baseball. His father allowed him to indulge his passion, hoping perhaps that the boy would get it out of his system - but when Cobb was 18, his father was shot to death. By his mother. He made his major league debut three weeks later. His father had told him not to come home a failure and Cobb played with a fury and desperation that suggested he thought the old man was still watching.

Most of us know Cobb has the highest career BAVG of anyone who ever played the game, and we're possibly not all that impressed. Even if that average was .366 - come on, it's impossible not to be impressed by .366, it's a ridiculous number for a lifetime average. Still, we're all aware that the highest BAVG is absolutely not the mark of the greatest offensive player, and are somewhat puzzled that people took it so seriously in years past. But they did so for a reason. Things were very different in a game without home runs, and in such a game the man with the highest batting average usually was the best hitter. Cobb led the AL in BAVG twelve times, and in eleven of those seasons he also led the league in OPS+. (He was second the other time, to Boston's Babe Ruth.) In those seasons when Cobb wasn't the league leader, it was some other AL hitter who was achieving the same double - Lajoie (three times), Tris Speaker, Elmer Flick, George Stone.

Cobb was as complete an offensive player as a man of his time could possibly be. I once suggested that Ichiro Suzuki came as close as anyone (not very close, to be honest) to Cobb among modern players - but Suzuki was strictly a singles hitter. So were Rod Carew and Tony Gwynn. Ty Cobb was not some little guy who slapped at the ball and ran like hell. He did that sometimes, but he was a big man who also swung hard at the ball and hit doubles and triples, lots and lots of them, as well as singles. By the standards of his era, he was one of the game's great sluggers, and I believe he would have been a great slugger had he been born in 1986. He was 33 years old, with fifteen seasons in the majors in 1920, when Babe Ruth began to change everything. Cobb scorned the new way of hitting - he was proud of the way he played, he didn't want to change - but I have no doubt that he would have been very, very good at it if that's the way he had learned to play. He led his league in OPS+ twelve times, and only Babe Ruth can match that - not Bonds, not Williams, not Hornsby, not Mantle.

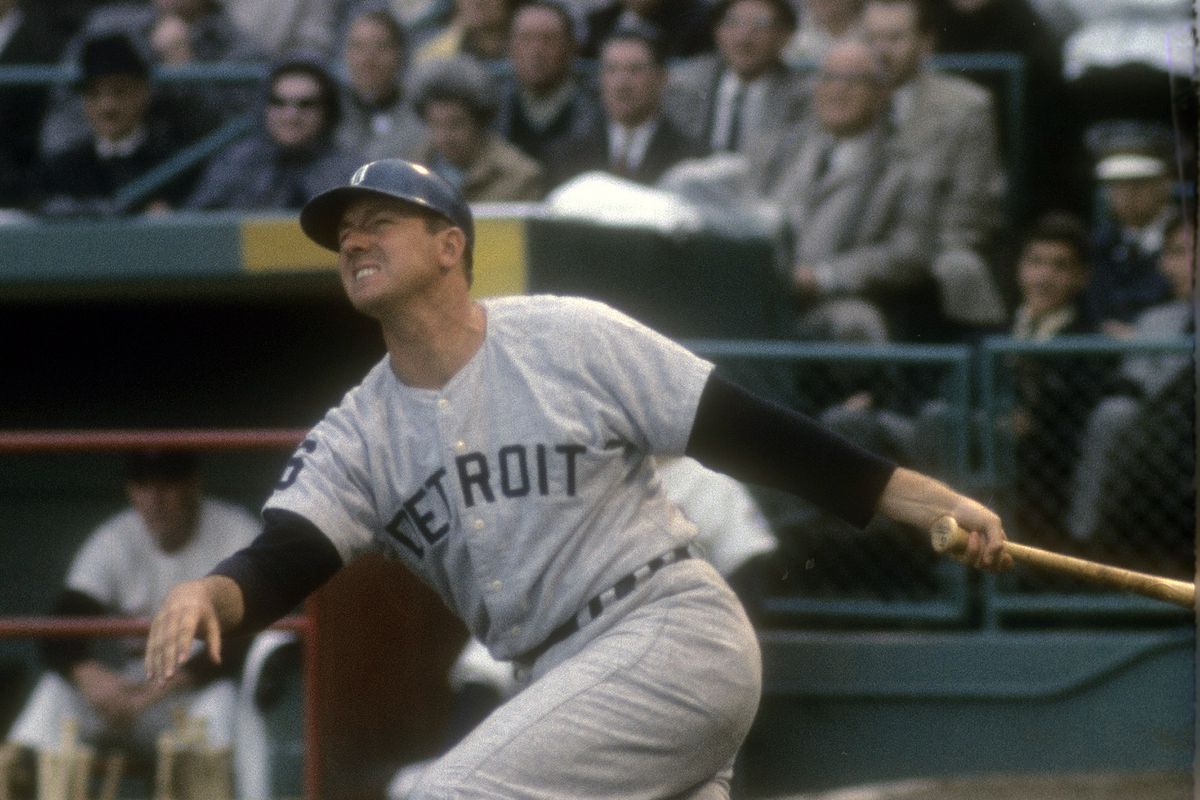

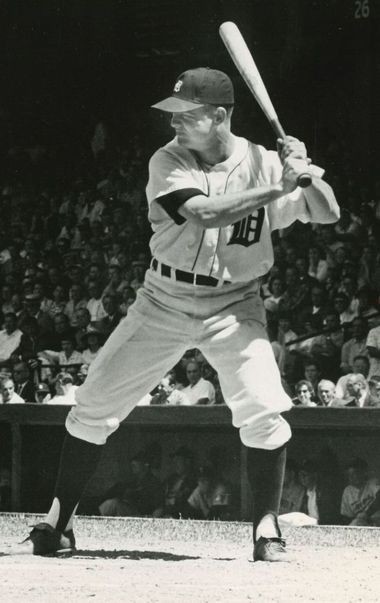

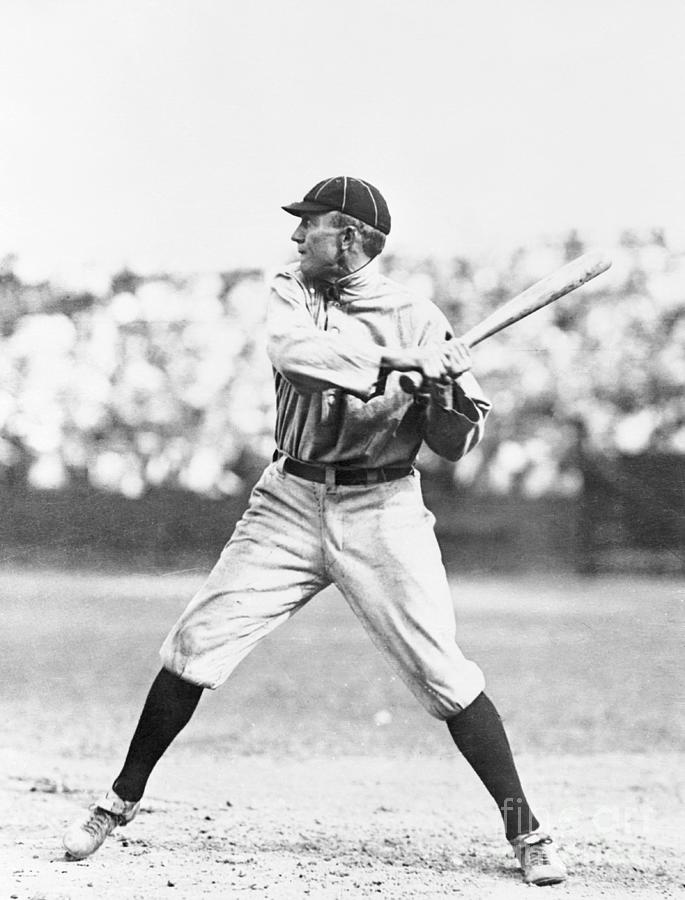

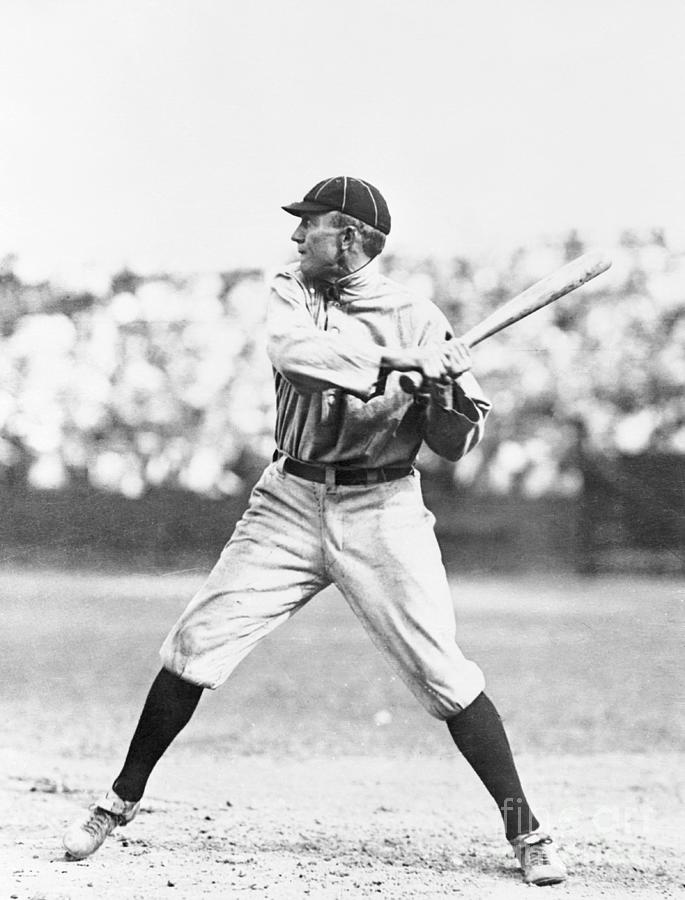

It's been 93 years since he played a major league game. No one who actually saw him play would ever forget the experience, but there can't be many people still alive who did. Most of the records he held when he retired have since been broken. Even so, all these years later, just one man has had more hits. Just one man has scored more runs. While he had taken little interest in his formal education, he possessed a formidable native intelligence - he would become a very rich man in later life from a series of canny investment decisions - and he applied that intelligence to the game. He never stopped looking for an edge, for some advantage he could exploit. It's difficult to get a sense of what he was like on the field. He did indeed hold his hands apart on the bat as he awaited the pitch - but he generally moved one of them before he actually swung at the ball, either to choke up and put the ball in play, or down at the end to take a full rip at the pitch. (As you can see in the first picture.) But there's so little footage of him. Most of what we have are still photos of some guy flying around the basepaths clad in the baggy uniforms of the day. Ty Cobb was a tall and slender man, a fierce and shrewd competitor, gifted with dazzling speed, and one of the greatest hitters to ever swing a bat. An amazing, spectacular baseball player. There has never been anyone else like him. Ever. Not even close.

10 comments

https://www.battersbox.ca/article.php?story=20210728174433398